More than once over the years we’ve had discussions in the roguelike development community regarding the idea of “backtracking,” and with good reason: whether or not to allow it has quite a lot of implications!

Here we’re primarily talking about the player revisiting earlier floors on their journey, rather than backtracking within a single map (though I’ll cover that topic a bit separately at the end), and our discussion focuses on roguelikes of the dungeon delving variety, since open world games generally allow backtracking by default.

Examples

Let’s open with a sample cross section of the types of map transitions available in the roguelike space:

- DCSS: Floors generally contain multiple stairs which lead to either the next floor or back to the previous one. The majority of roguelikes fall into this category, although not necessarily the multiple stairs part.

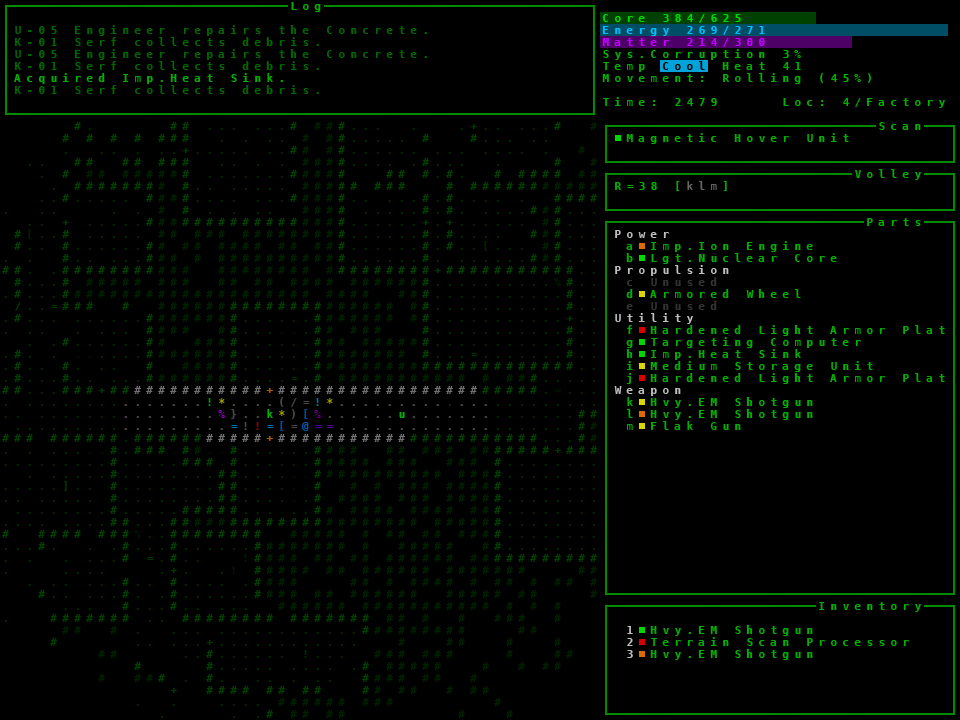

- Cogmind: At the other end of the spectrum, some roguelikes don’t allow backtracking to earlier floors at all. This group also includes DRL/Jupiter Hell and Infra Arcana, but it’s a pretty small group overall. (DCSS variant “Hellcrawl” removes the up stairs from that game, notably increasing the difficulty.)

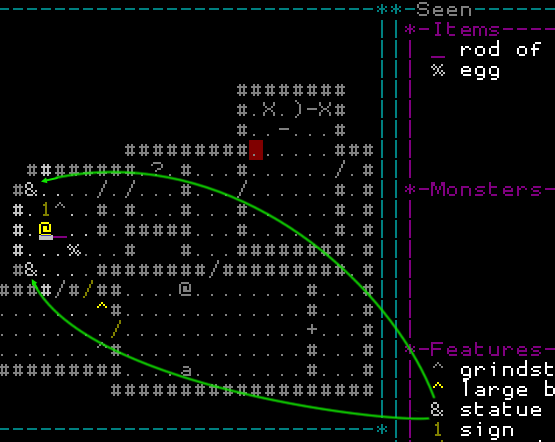

- Moria/Angband: These are unique in that backtracking is allowed, but by default it generates a new floor each time! Although not true backtracking in every sense, it will naturally count in some ways. The approach is quite thematic, in any case, getting lost exploring the Mines of Moria, or maze-like fortress Angband :)

Heading back up some stairs (‘<‘) in Moria for your very own “I have no memory of this place” moment.

- Rogue: Interestingly, in the original Rogue backtracking as a part of the ongoing diving process was not a thing! You can only proceed down stairs until you acquire the amulet, then you can finally go up stairs, but each floor in the return direction is generated anew, essentially requiring playing through 51 floors to beat the game!

One traditional reason it might make sense for roguelikes to allow backtracking is because the goal is often to reach a destination then escape back out, not unlike your typical RPG dungeon adventure.

Different games handle the escape in a variety of ways, perhaps throwing some kind of new challenges at the player along the way, for example being intercepted by powerful monsters the entire way in DCSS, or being harassed on the way out of Angband by an angry Morgoth after stealing one of the Silmarils from his crown in Sil (or the newer Sil-Q).

The Ground Gives Way has an especially interesting approach, having the dungeon’s statues come to life after you acquire the trombone relic (yes, trombone) at the bottom, and you have to escape without being killed by the animated statues or whatever other creatures might still be in the way because they weren’t dealt with before. The interesting part is that you can see all these statues on the way in, foreshadowing potentially difficult bottlenecks on the way out (assuming you can’t directly confront and outright destroy all the living statues, a decent assumption for many builds).

These statues will come to life on the way out and try to stop you--better have a plan when the time comes! (Tip: If you put down the trombone they’ll stop following you, giving you an opportunity to deal with other issues, rest, or prepare in other ways.)

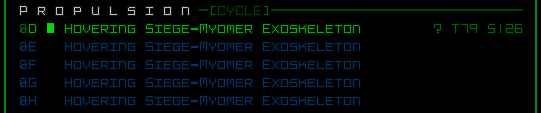

By comparison, Cogmind is purely about escape, starting from the inside, so there’s no reason to go back as part of the conclusion.

To Backtrack or not to Backtrack

I was originally going to divide this article into two sections highlighting the “advantages and disadvantages” of each approach, but it’s not always clear whether a given mechanic or consideration would neatly fall under one of those two categories, especially given that additional design adjustments can turn a drawback into a positive, or otherwise mitigate issues, so it’s more a question of simply examining the implications of a particular choice and accounting for it in a game’s wider design. So instead we’ll take a topical approach.

Realism

Being able to backtrack is generally going to be more realistic in the RPG sense--of course your character should be able to go back and pick up that item they left behind, or fight that enemy that scared you away before. Plenty of roguelikes are designed as CRPGs first, so it makes sense they’d want backtracking for this factor alone, if anything.

Some roguelikes don’t go heavy on realism, in which case backtracking for this reason can be considered a non-issue and solely a decision to be made within the greater mechanical design, though this does mean progress ends up feeling gamier overall.

Since thematic plausibility and lore are quite important in Cogmind, I added reasoning for why you can’t backtrack, so that’s an option as well. In general it’s good practice to try to explain anything that doesn’t work as players might otherwise expect, and the one thing you can count on setting player expectations is realism! Realism is optional (these are games!), but ideally we want everything to at least make some sense within the context of the game world itself.

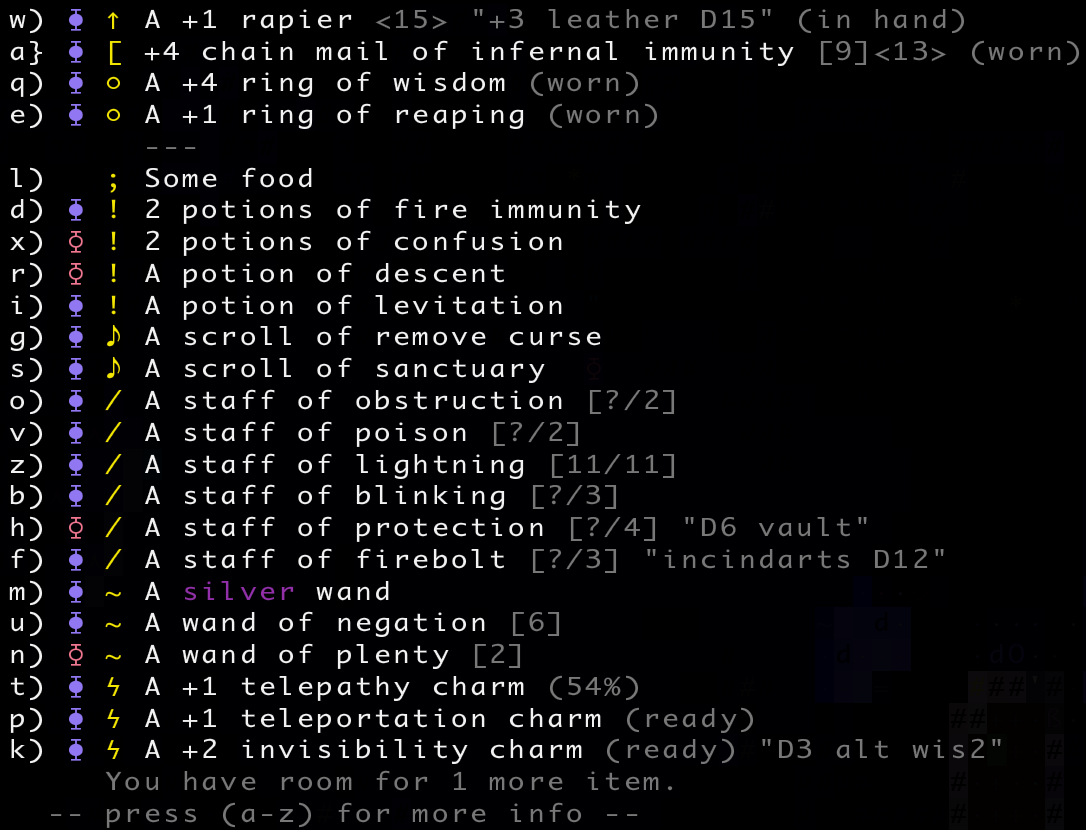

Stashes

While on the subject of realism, it also makes plenty of sense you can go back to collect resources left behind earlier. In a game setting, though, this can be quite an annoyance from a design perspective (harder to balance!) and is likely to either become a player crutch or lead to tedious optimal play (a topic I covered in my game design philosophy article).

As a result, you sometimes see developers coming up with ways to address issues arising from players creating “stashes” of items to return to. DCSS has an interesting historical summary of changes related to its stashes, including methods to decrease player reliance on them.

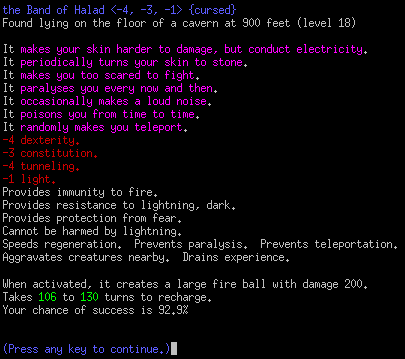

As a fully item-focused roguelike (in that items are everything to you, with no other types of character progression), stashes used to be extremely useful for an optimal player in TGGW. That’s before the aliens showed up :)

Aliens arrive while you’re napping to steal things the player has touched, and you can sometimes catch a glimpse of them running away with an item, or theoretically even try to stop them before they teleport away, but it’s pretty tough, so you’re highly encouraged to always keep anything you want to use for the long run. Under this scheme, strategically the player may also opt to leave an item on the ground, untouched until they might want it, but it can be hard to justify that decision since in many cases if it’s a quality item you won’t be entirely sure what specific item it is until you’ve picked it up to identify and it’s got that human scent all over it :P

Caught red-handed, but good luck stopping them.

An alternative approach to stashes is to simply embrace them as part of the design, even going so far as to outright give the player a safe location to stash extra items they don’t need at the moment, for example in a town. Heck, throw in shops to visit while you’re at it :D

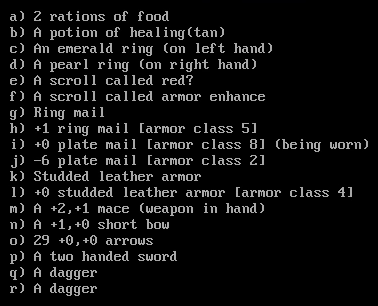

An Angband town, which serves as a hub to return to for stashing items, or shopping.

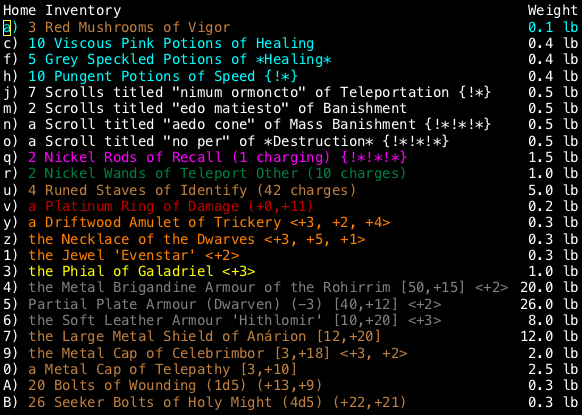

An example of a player home inventory in Angband (taken from here among the great LPs by TooMuchAbstraction).

Or an even simpler approach: just give the player a practically infinite inventory :P

Of course stashes aren’t always an issue--depending on how the game works there may not even be a use for them, although the reason it comes up so often in roguelikes is that the genre is overall fairly item-heavy, not just different useful gear but especially consumables, which leans towards stashes being a thing.

If tight enough, a roguelike’s typical food clock or other similar feature pushing the player forward might also serve as a suitable countermechanic, or impose prohibitive costs on abuse/overuse of stashes.

Grind

Grinding as a strategy, or even existing as a possibility, is pretty unwelcome among modern roguelike fans. Not universally so, to be sure, but grind tends to be more of a roguelite thing.

Preventing backtracking cleanly cuts out a number of potential types of grinding (such as returning to fight weaker enemies to maximize XP or resources), thereby serving as another feature contributing to a player’s forward momentum.

Of course for some roguelikes, grind is an acceptable part of the gameplay for those who want it. No doubt the grindiest of classic roguelikes is Moria/Angband, and this honor is a direct result of backtracking as per the mechanic described earlier. Simply going up and down stairs to generate new maps (“level scumming”) gives access to theoretically almost anything that can appear at a given depth, so a player can use this to not only raise more levels from repeated combat before pressing forward, but perhaps even more in the spirit of ultimate grinding, you can keep regenerating maps to search for specific items.

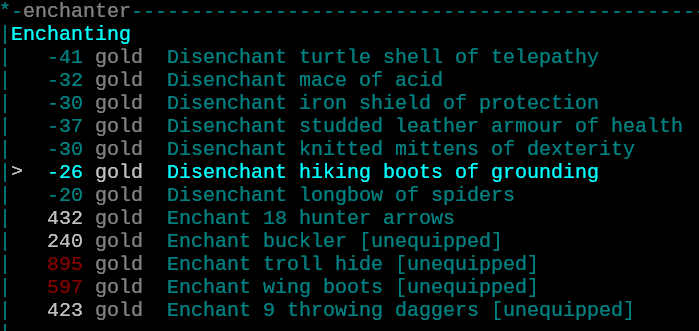

In a way Angband further facilitates some of the grinding process with its “level feeling” text on entering a map, revealing how dangerous the floor feels, how good the items potentially are, and maybe even a “special feeling” like “You feel strangely lucky…” or “You have a superb feeling about this level” to indicate additional features such as a vault.

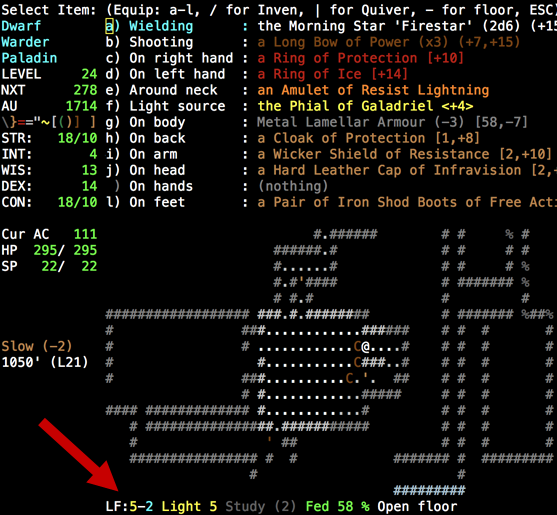

Then in 2015 the Angband maintainers doubled down by making the grind even more player-friendly, adding level feeling information directly to the status bar in numerical form.

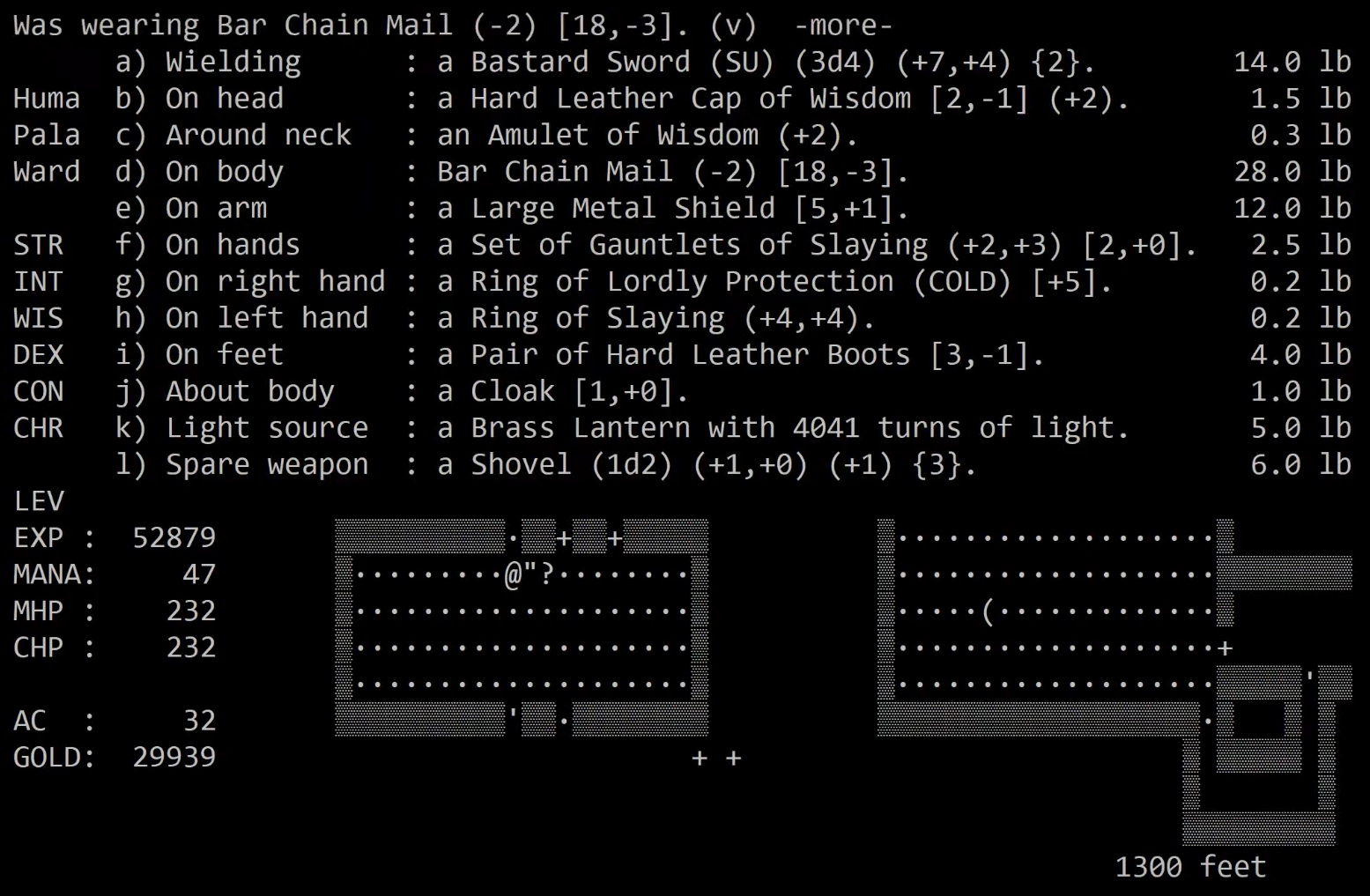

Angband level feeling indicator “LF:X-Y,” where X/Y refer to the danger/treasure level on a scale of 1~9. Y even shows as $ if an artifact was generated on the current floor.

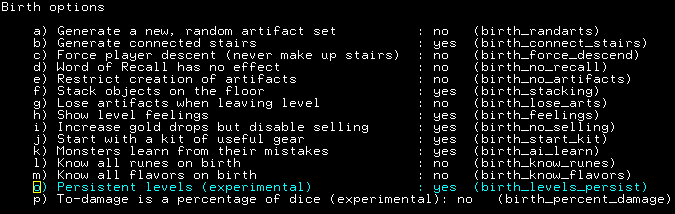

Well fast forward to 2017 (27 years after Angband’s first release) and a new option is added to the game, one that changes everything: persistent levels!

Birth options menu during Angband character creation. Even after five years, birth_levels_persist is still considered an experimental feature with potential bugs to work out.

Yes it’s optional and clearly not the default considering it removes one of Angband’s defining features, but this addition made the game playable for some who hated the original incentive to grind, dangling there like a carrot at every depth, and also gave existing players an alternative way to enjoy the content. Some technically were already playing it that way before, without the grinding, but enforcing that conduct can take a lot of self-control, especially in a game with permadeath ;)

Anyway, Angband has taken up a good chunk of the article so far because I think it’s an interesting study for this topic, considering you can experience two very different approaches to backtracking in a single roguelike. There’s a lot of conversation out there about how different types of players prefer one or the other.

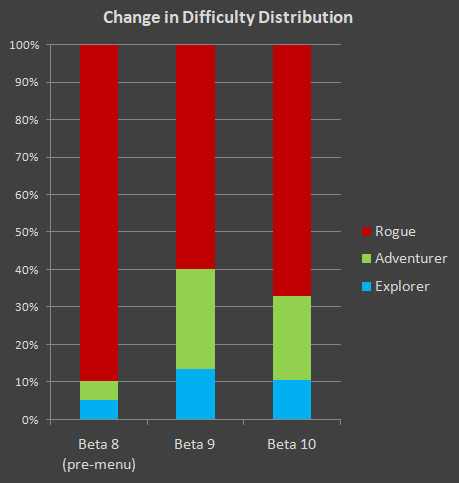

Difficulty

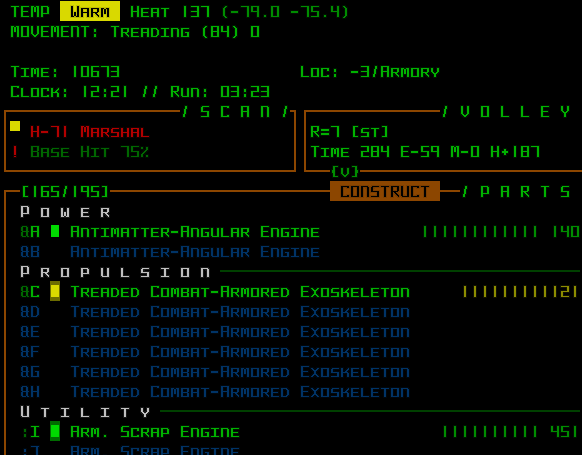

For the same reason backtracking might make way for grinding, it also serves as a way to help soften difficulty spikes, especially those that might occur immediately on entering a new (and presumably more difficult) map. If finding it hard to press forward after using the stairs, one could theoretically go back and switch to a different map (Angband), or approach the new floor from a different point (DCSS with its multiple stairs), or go grind more resources/XP left behind in earlier areas to help advance.

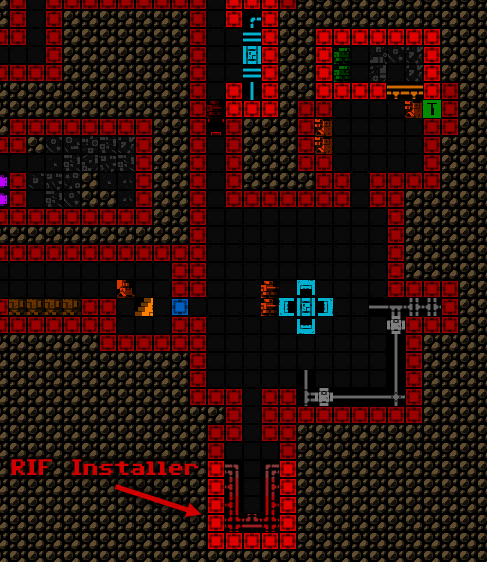

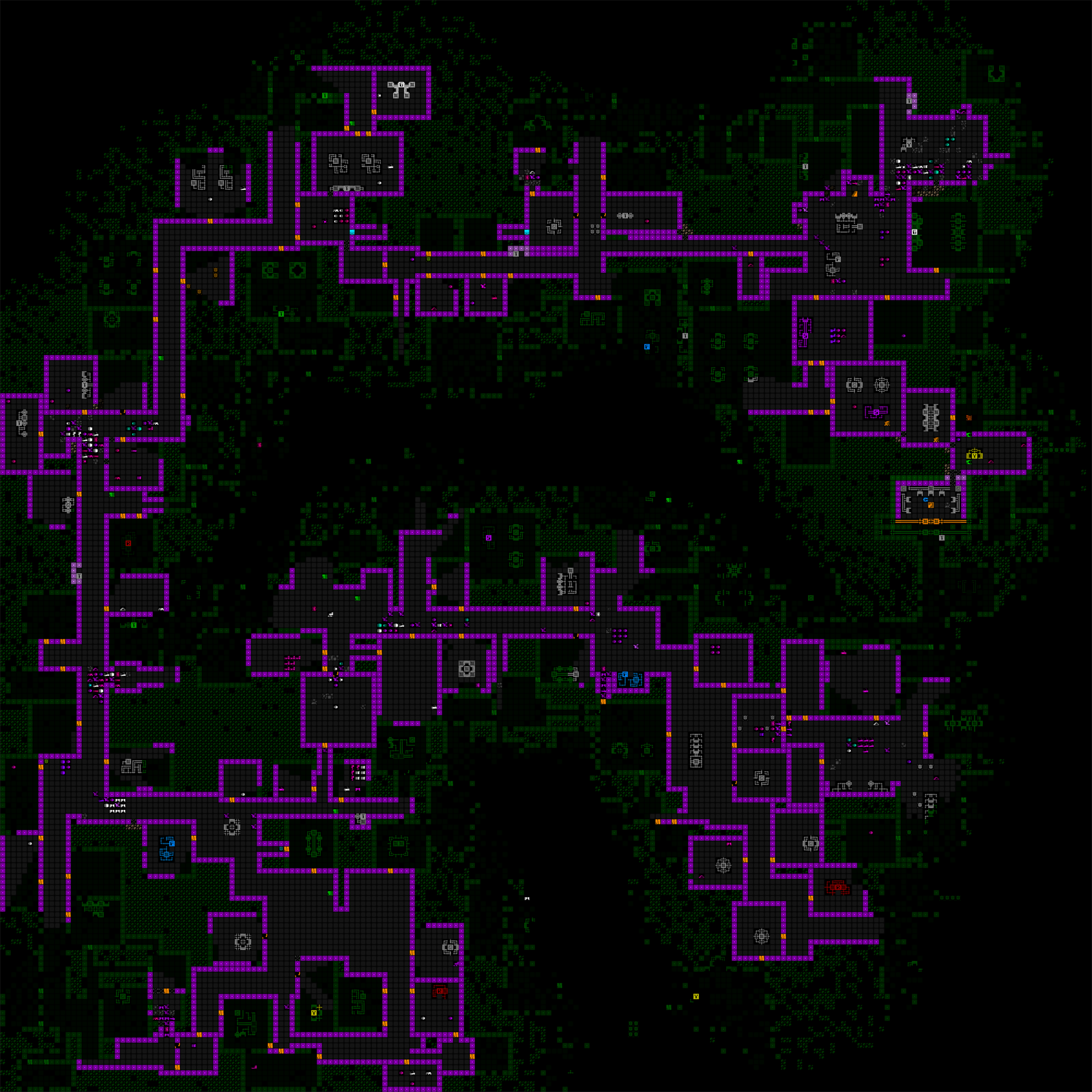

Cogmind has very large maps so this isn’t as much of an issue--you’re generally not going to full clear all maps anyway, and there are usually many possible routes within a given map (especially counting terrain destruction, employed liberally by players :P), so encountering a dangerous bottleneck required for progress is not all that common. Cogmind also has “spawn protection” on main maps explicitly to give the player more breathing room on entry (though not in optional branch maps, where ambushes are indeed possible! just an extra part of their potential danger in exchange for the rewards within).

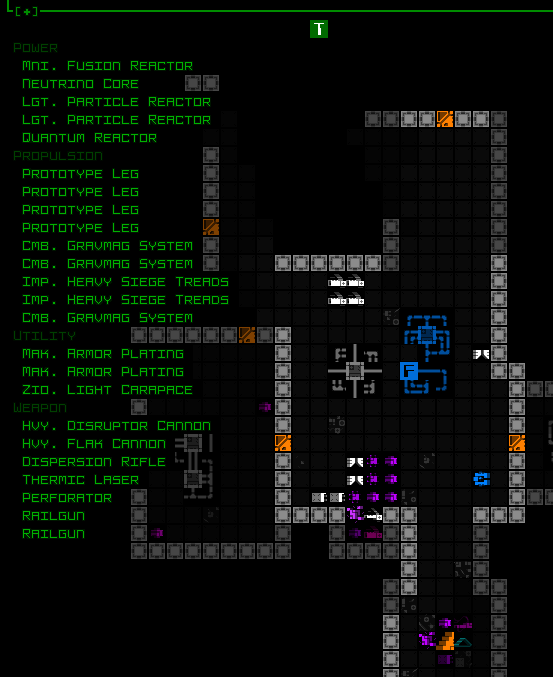

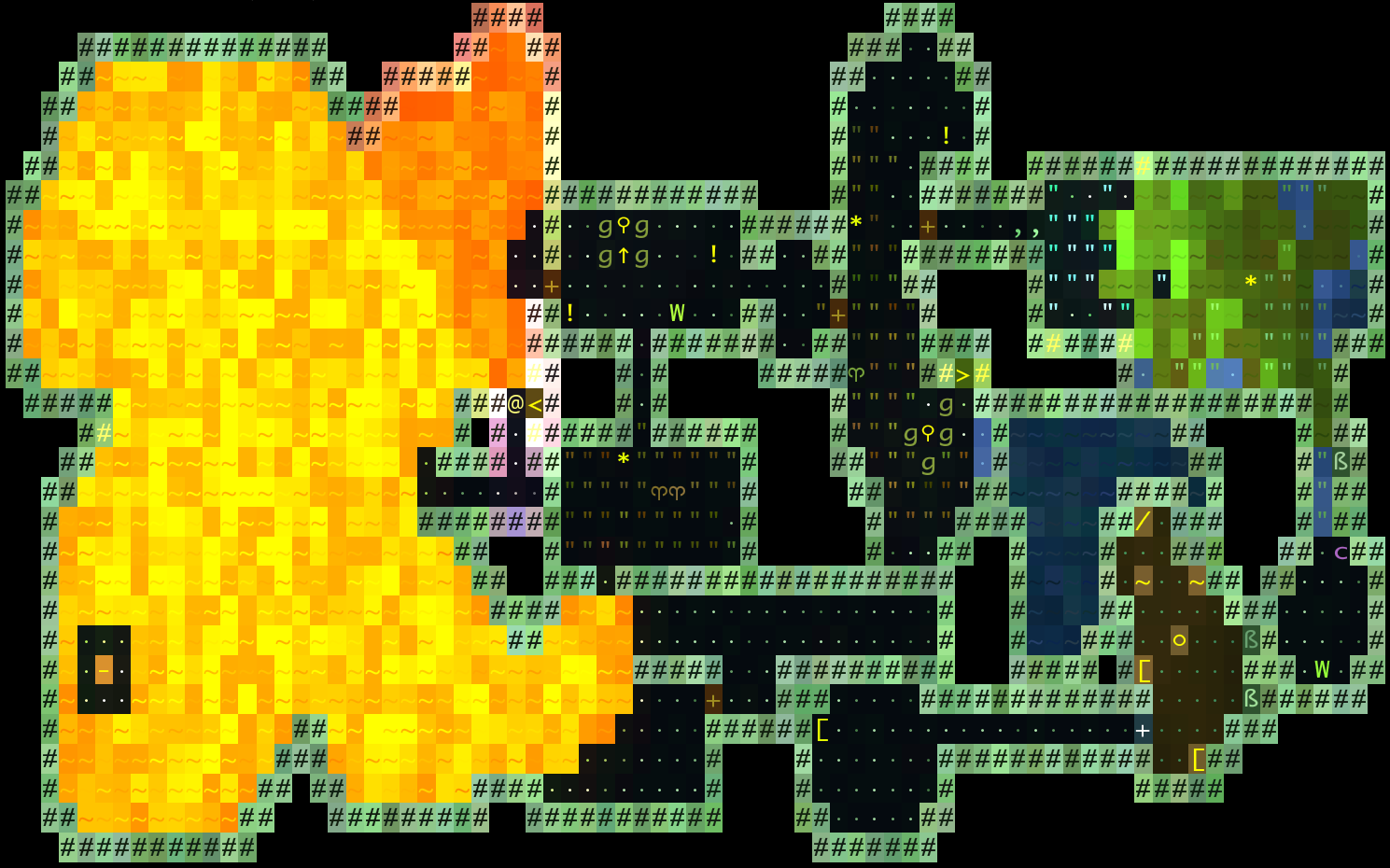

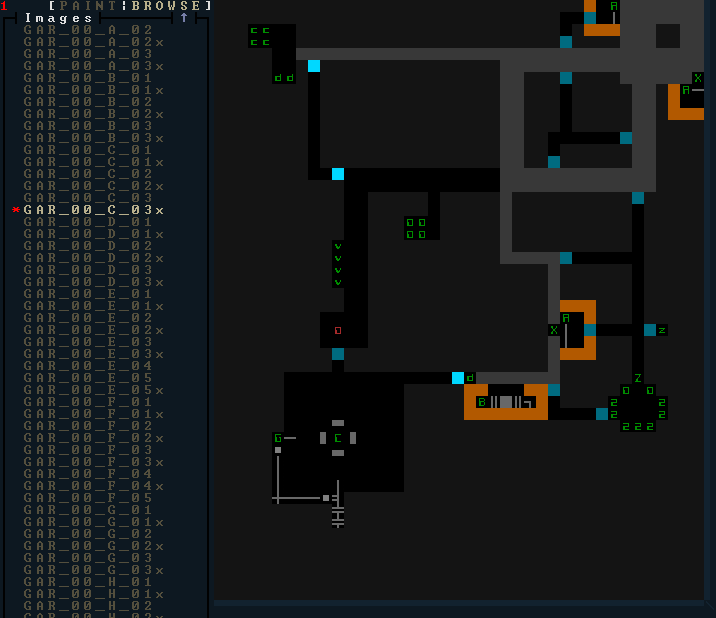

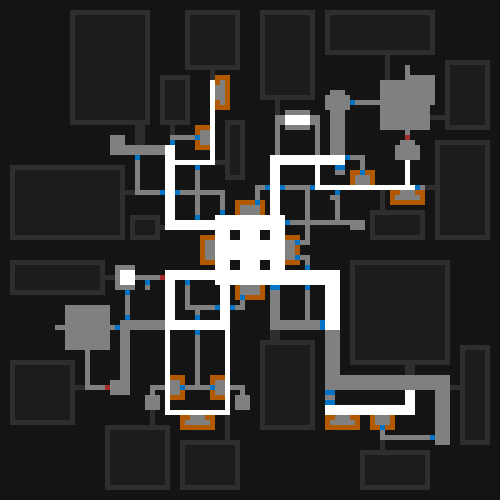

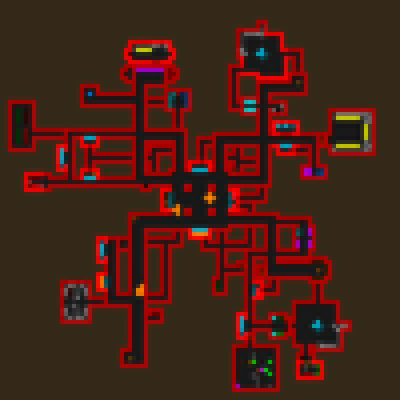

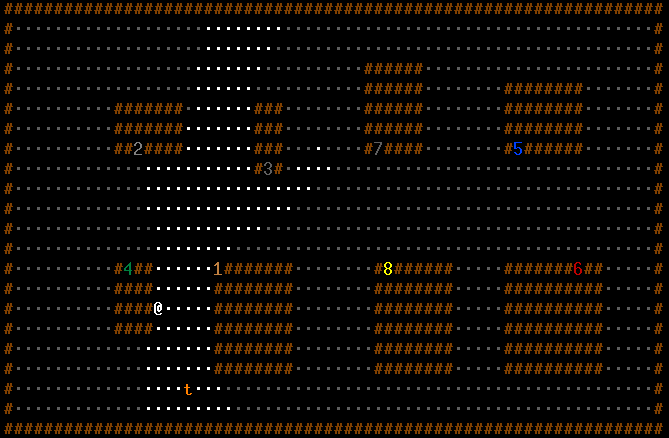

It’s not usually in your best interest to explore the entirety of every map in Cogmind--they’re big and you’re likely to lose more than you gain from doing so. Above is an export of one player’s unusually lengthy journey across a large swathe of a 200×200 map in search of a particular destination (a desired exit).

Zorbus is a good example of difficulty spikes on entering a new map where backtracking is not allowed. You’re in for a crazy ride almost any time you take the stairs in this DnD-style roguelike, especially given the pretty significant jump in danger from map to map, where all the enemies are higher level than you until you catch up, and thin them out a bit first.

My party in Zorbus getting ambushed by all manner of powerful enemies coming from the west, south and east right outside the opening room (clearly the NPCs know what’s up!). Large battles are common on entering a new Zorbus map. They will spot you, hunt you, tell their friends, then hunt you with their friends :P

This aspect of Zorbus was softened a bit following response to the game during its wider release on Steam recently, at least protecting the player from being right near the level boss on entry, which could understandably be pretty devastating xD

Stairs

Stairs are an interesting design issue in roguelikes regardless of which backtracking rules apply.

Without backtracking, players are stuck with dealing with whatever they encounter on the other side, though hopefully have tools for managing sudden difficult situations, such as immediately teleporting away, or perhaps specifically preparing for a potential ambush before entering.

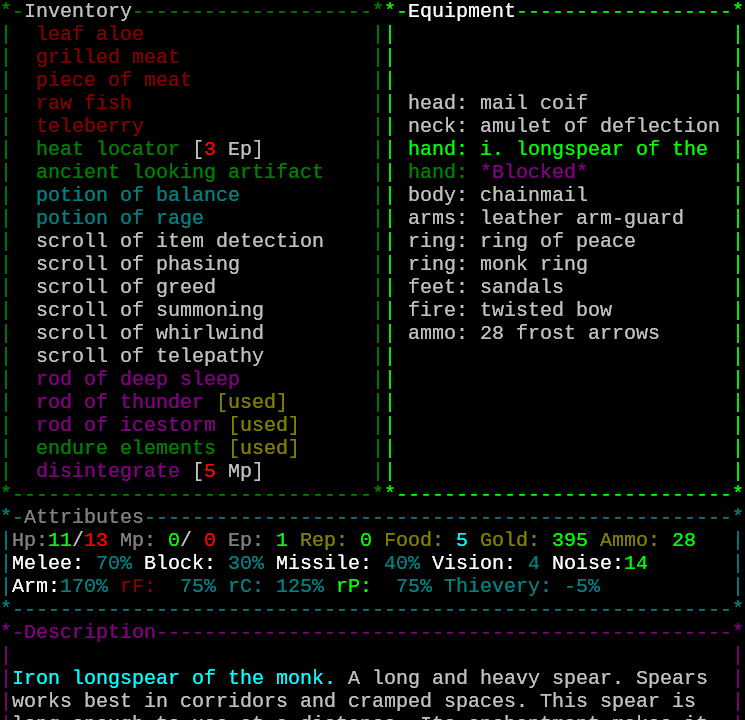

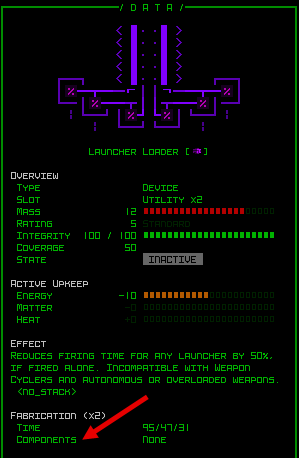

In Zorbus, blinking away is a common strategy for escaping dire threats. Cogmind doesn’t have easy/unlimited teleporting, but also has the spawn protection rules to avoid issues in many areas, and where those don’t apply, a player might indeed decide to enter prepared for a close-range ambush, like with a launcher at the ready :P

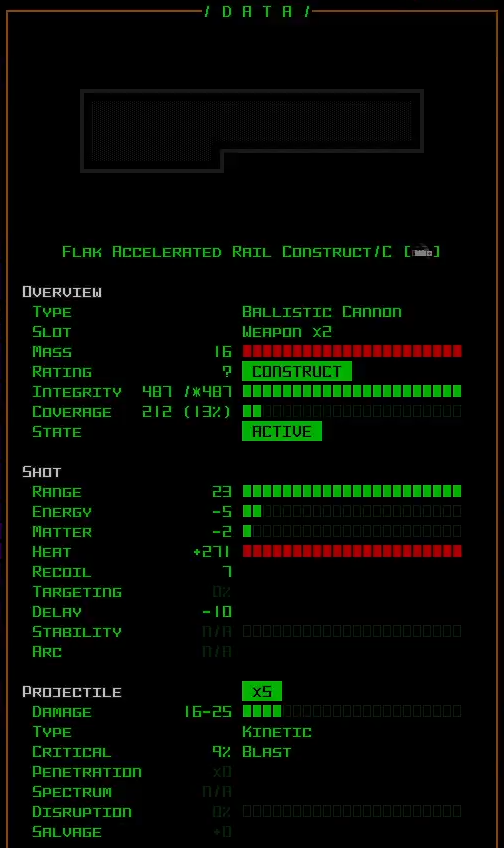

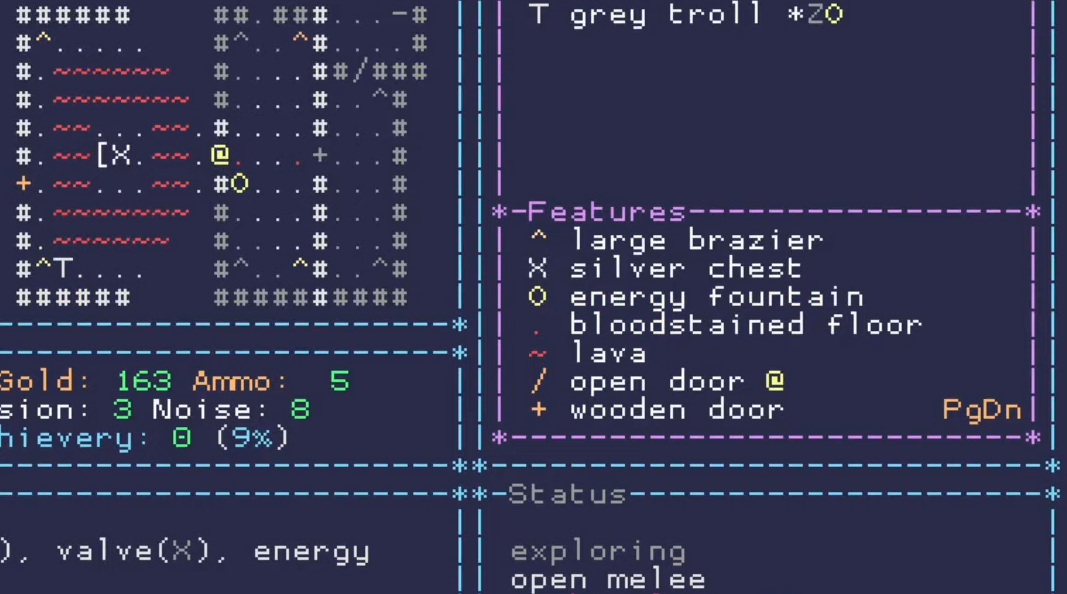

In most cases I feel safer entering caves with a launcher out to blast any group loitering on the other side. (It’s less of an issue for some builds, though, or if traveling with allies.)

With backtracking, developers have the unfortunate task of addressing “stair dancing,” or repeatedly using stairs as an easy escape option, even as part of localized combat tactics. Do enemies follow through stairs? How far? What else do they do if they see a player leave but don’t follow?

Various solutions, or pieces of a solution, include:

- Nearby enemies can follow via stairs, for example in DCSS and Caves of Qud, but in games that do this there’s always the problem of just how far away will enemies follow from? It’s often still optimal if you can use this tactic to split them up, or at least temporarily break LOS to some while fighting others. Qud has an interesting addition here where you can actually use the stairs then stand on them to fight enemies that are coming one-by-one, but it’s blind combat and you can’t see which one you’re attacking.

- Attach a resource cost to reusing stairs. For example drain stamina so the player is at an immediate tactical disadvantage after doing it, should enemies follow. Or using stairs takes more game time, further advancing whatever food/other types of clocks the game employs.

- Reusing stairs first gives nearby enemies free attacks of opportunity.

- Enemies that saw the player reuse the stairs wait nearby, then get the initiative/first strike on the player’s return.

- Teleport players after going back through stairs (a possibility in DCSS variant “bcrawl“).

- Make reusing stairs impossible while in combat (some TGGW stairs are called “twisted stairs” and behave this way, while others are normal, so traveling down the former might be more dangerous).

- Design such that stair dancing is meaningless. For example it was originally an optimal tactic in Tangledeep, but the developer later changed it so that all monsters heal fully heal when the player leaves, but the player doesn’t have passive regeneration.

Anyway, stair dancing is definitely high on the list of issues a developer wants to consider if backtracking is a thing. My own DCSS play and stair dancing experience (circa 2010) was a strong influence on Cogmind, in that it was the whole reason I decided I didn’t want backtracking at all, despite the other advantages of making that choice which I later came to appreciate (Cogmind was originally a 2012 7DRL, so the scope wasn’t imagined to be anywhere near what it eventually became--there were far fewer considerations then :P).

Design Control

For several reasons already touched on, removing backtracking affords tighter control over progression and mechanical design since map transitions serve as a hard cutoff, turning individual maps into more isolated units. Expanding on that, the designer now also has reliable points at which to determine specifically what the player has and has not done by then, a fact that won’t change going forward. While roguelikes of the hack-n-slash variety (uh, lots of them xD) maybe don’t care so much about this aspect, there are definitely some greater benefits to be had among modern games branching out beyond that style.

Being able to refer back to an entire immutable history of player interactions with prior maps and their content, developers are able to more easily build sturdy plot lines that are harder to disrupt, for example. In open-world CRPGs where you have plot and quests, I imagine many of you have had the experience of breaking them one way or another :P

I’ve written a lot about “Weaving Narratives into Procedural Worlds” before, and it would be vastly more work to achieve the same results if backtracking were possible, simply due a ridiculously large expanding web of possibilities. If you can visit NPCs in any order, or revisit earlier locations after later events have occurred, each new connection and route ideally needs to be accounted for, or risk feeling like a loose end. Alternatively, you could explicitly block the player from doing many of these disruptive things, which is less immersive, so we’re essentially trading in a potentially gamier “no backtracking” rule in order to ensure we can create more realistic interactions throughout the world, covering more of those bases in a satisfactory manner.

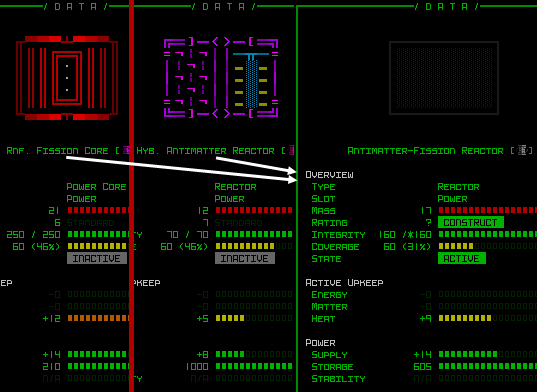

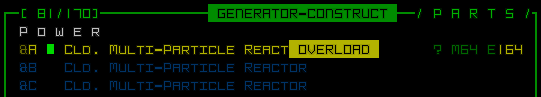

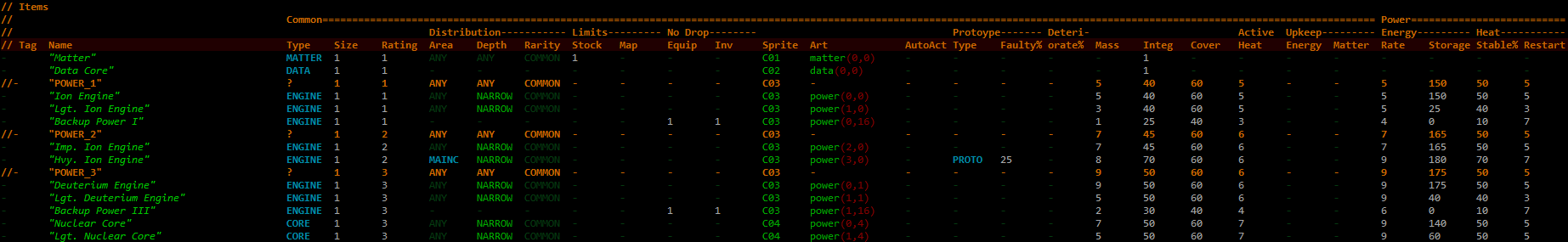

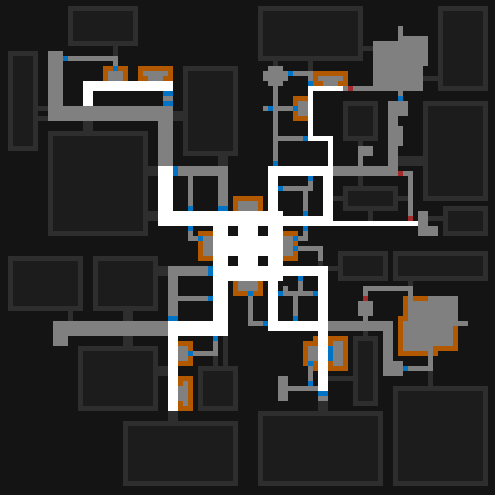

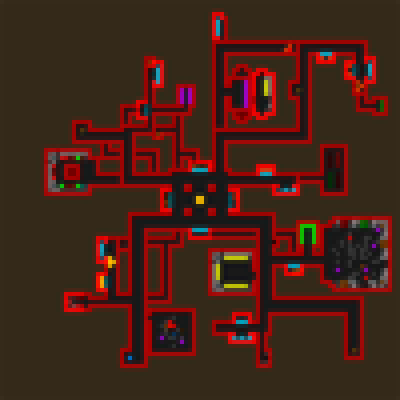

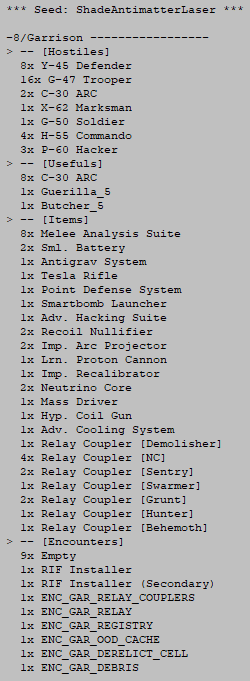

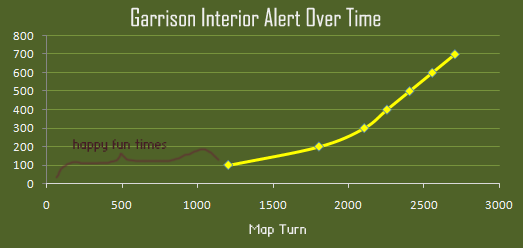

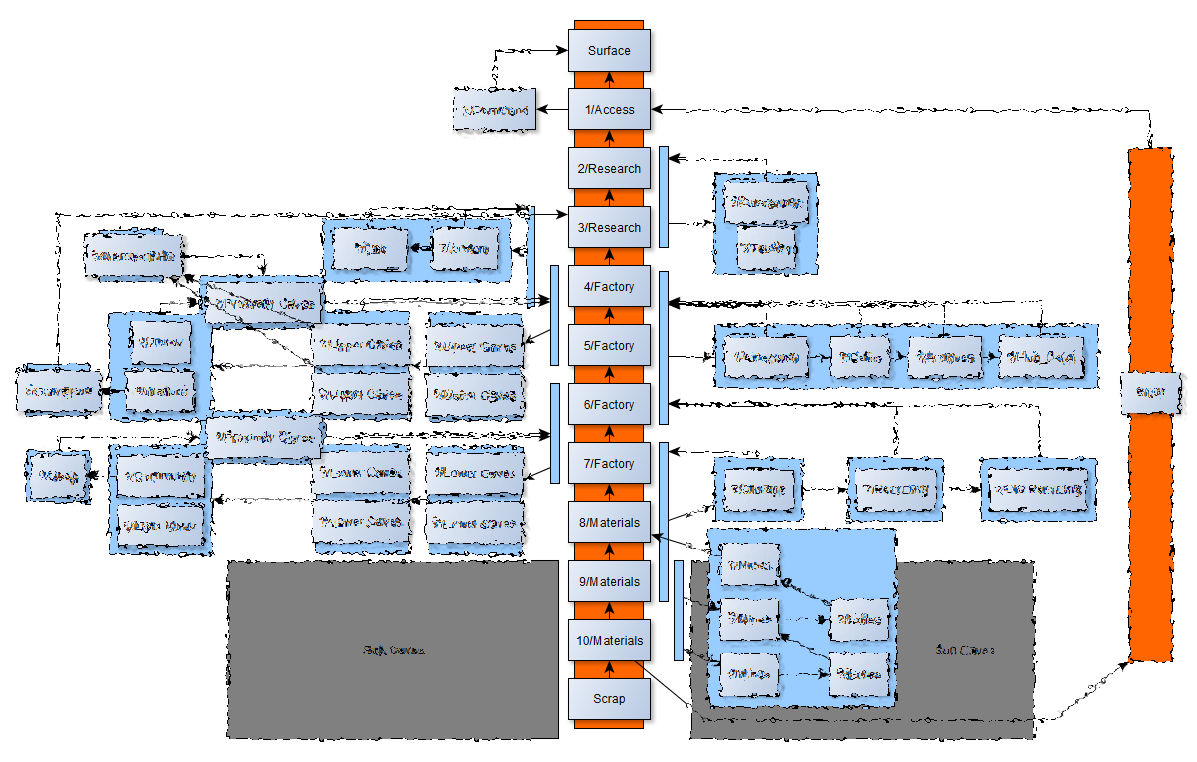

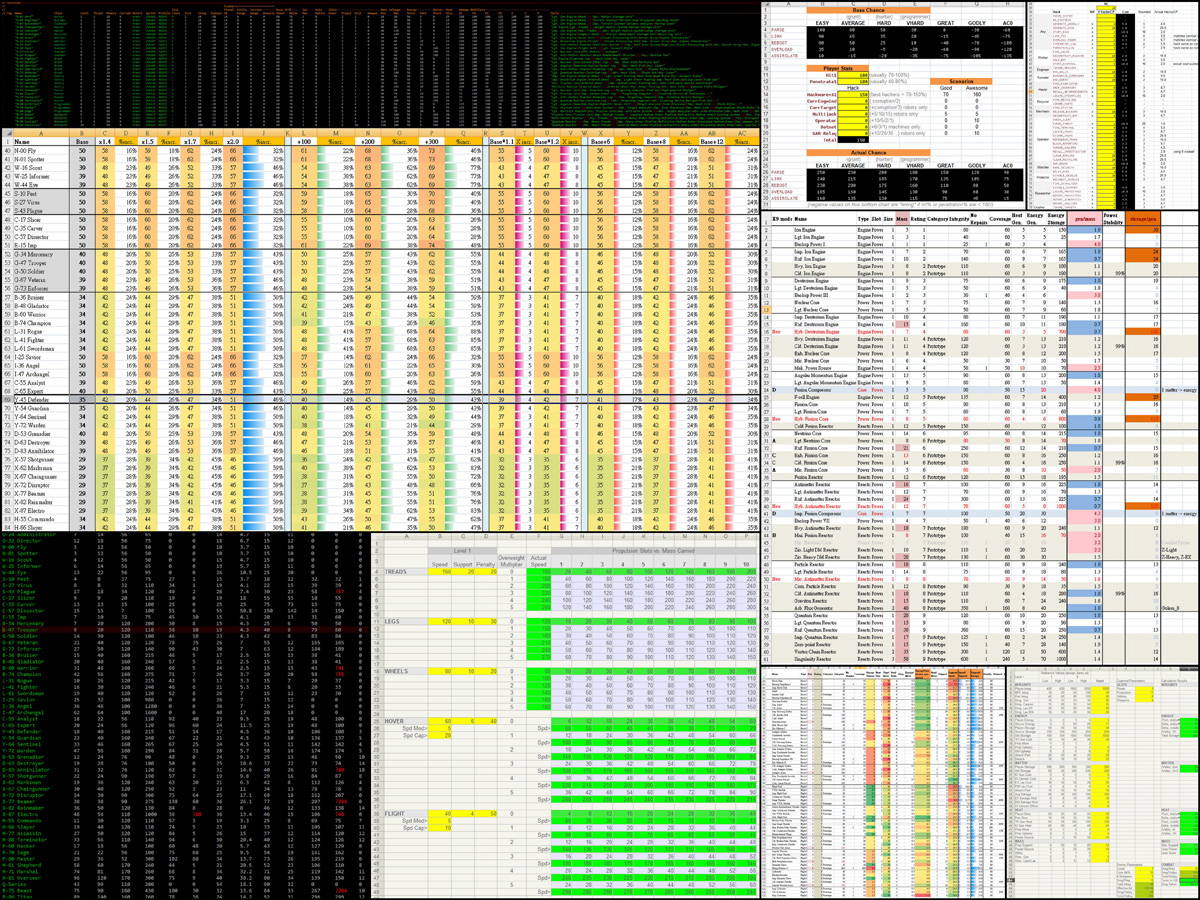

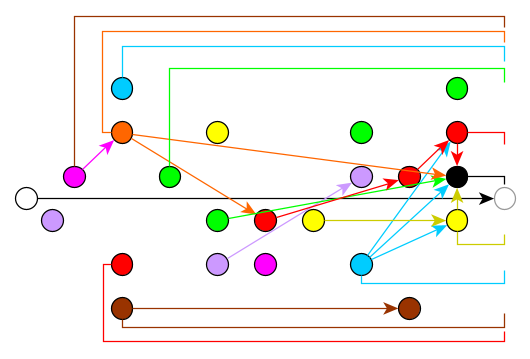

In cogmind the web of possibilities is already increasingly complex the further the player reaches, and that’s assuming players cannot revisit earlier areas. To demonstrate, below is an abstract visualization of Cogmind’s potential plot-related encounters with major NPCs. The game begins at the left, and progresses to a win at the far side. The story is tightly integrated into the gameplay, and many of these encounters have implications for later encounters, for the player, or for the world in general.

Major NPCs, colored by faction, showing those with a direct effect on some later encounter (arrows), as well as those with a relatively significant long-term impact on gameplay (bracketed length). And that’s just the major ones :P

Now for small-scale quests or one-off minor NPCs, backwards travel is not a big deal, but for anything on a grander scale, the control afforded by forcing the player forward keeps the amount of work required to a sane level. It’s certainly still doable, after all there are open-world roguelikes, but it somewhat limits the types of interconnected events and content you can add, or the level of detail added to each one, unless there’s enough dev resources to account for and build all the unique permutations, or simply have those possibilities take a more generic form (i.e. integrate them into generic faction-based systems and revolve more around dynamic relationships rather than building a compounding handcrafted story).

As far as story goes there’s definitely something to be said for allowing the player to revisit an earlier location and find a new experience there, but I’m willing to sacrifice that possibility for all the other benefits.

In Cogmind I can safely introduce extreme changes to the player’s capabilities or relationships without having to worry about the implications on earlier areas (of which there would be many, making it really hard or in some cases impossible to implement a number of my ideas :P). Also because Cogmind has a branching world structure in which we know that not all branches will be visited, the player is forced to make permanent choices about where they will travel for benefits (or challenges) XYZ down the road. Linear dungeons don’t need to consider this sort of thing, but it’s quite important for branching dungeons, where without backtracking we’ve suddenly built a new layer of design control directly into the world structure itself.

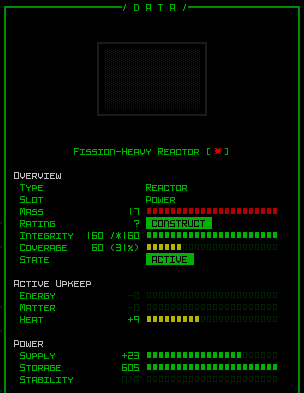

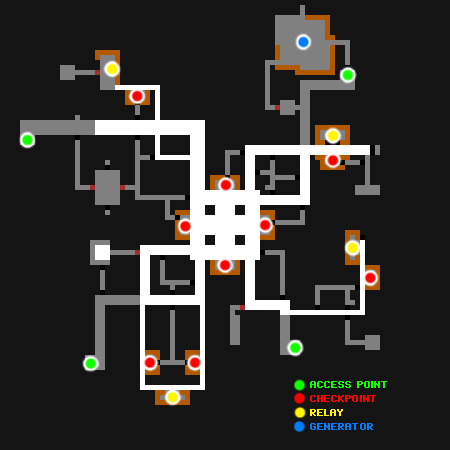

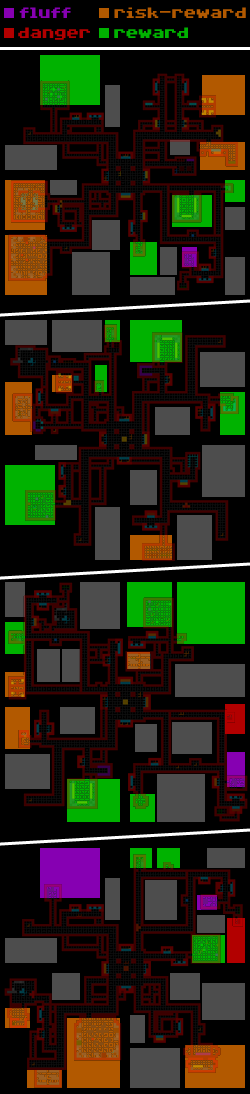

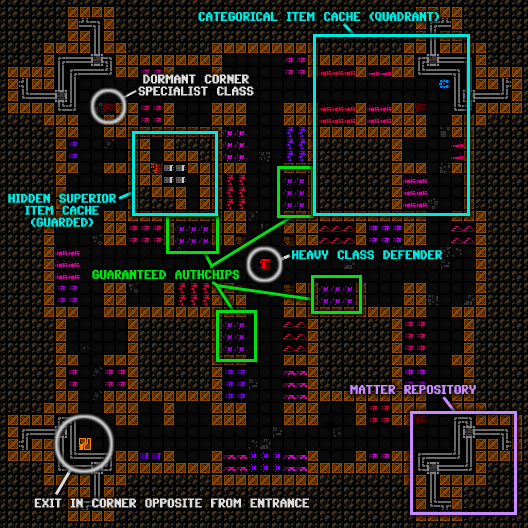

Sample Cogmind world map, in which the player can choose their route but only move upward or sideways to a new map. (This version excludes a number of spoiler areas, especially towards the end--a full-size version and more info can be found at the beginning of my series on spicing up Cogmind’s primary maps.)

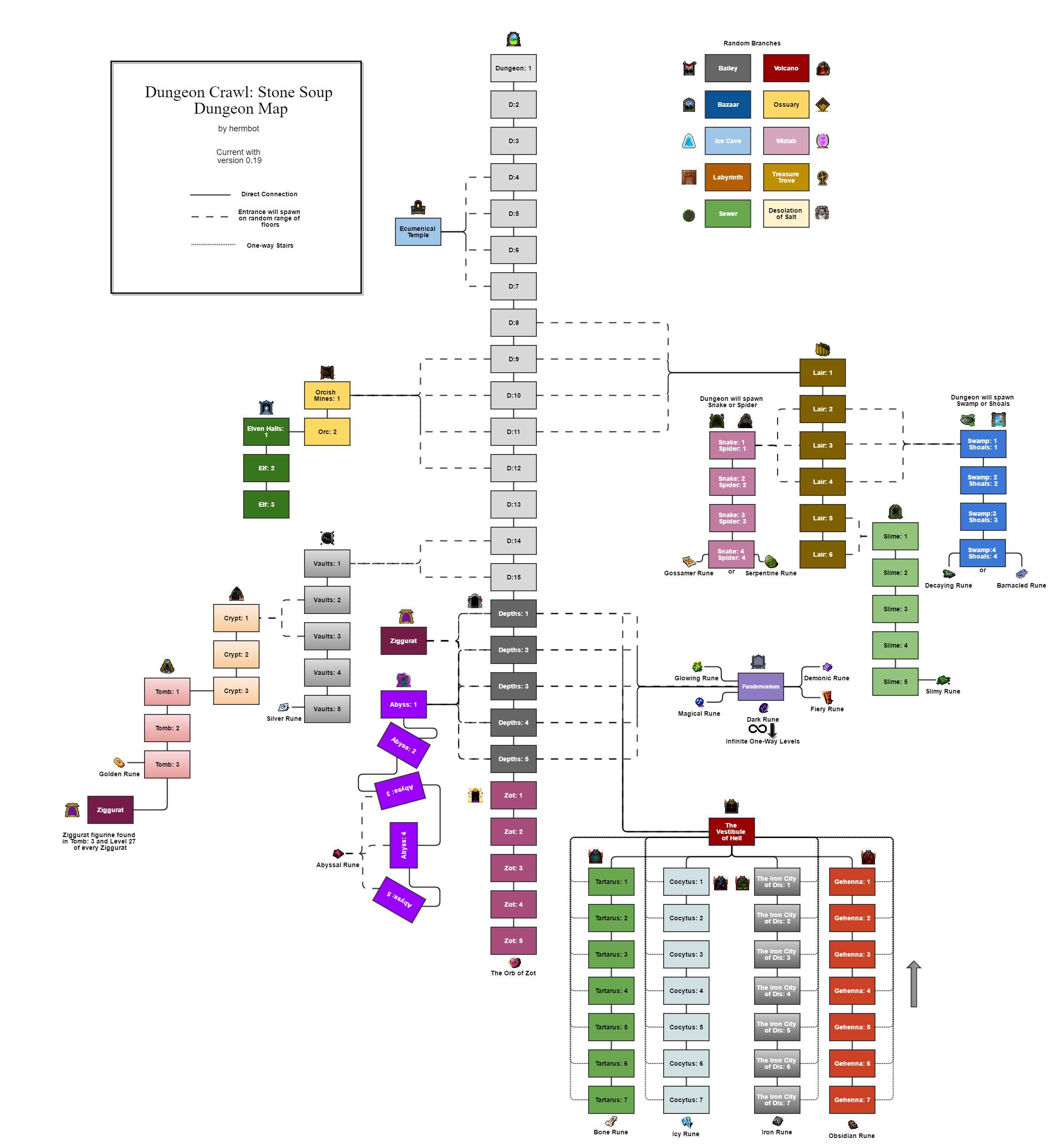

Compare to DCSS, which also has a branching structure but allows backtracking, meaning players instead have a range of non-mutually exclusive options to combine, or return to later if desired. More freedom for the player, less control for the dev. Not that strong controls are necessary, of course--it’s built with this level of open-ended freedom in mind.

A DCSS dungeon map linked from the wiki. It’s fairly old since it’s from version 0.19 (2016!), but it gets the point across (open image for full size).

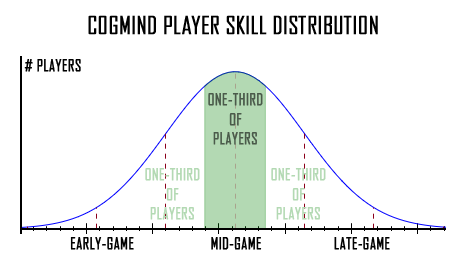

Meta Complexity

On a larger scale, new maps serving as a cutoff point also allow players to repeatedly unload some previous content from memory. It’s just their current state and resources, and the path forward--less about traveling back and forth, and more about exploring the unknown, which in turn happens to be more in the roguelike spirit (says me :P) (but think about it!).

Backtracking and the implication that an optimal player probably needs to be keeping as much useful run background info in their mind might add yet more overhead, especially if one stops playing for a while and resumes a run in a later session--in some cases it’s much easier to pick up and continue an unfinished run in a roguelike that doesn’t have backtracking since you just check your character info and take a look at the map (where you may have even efficiently stopped right at a transition point).

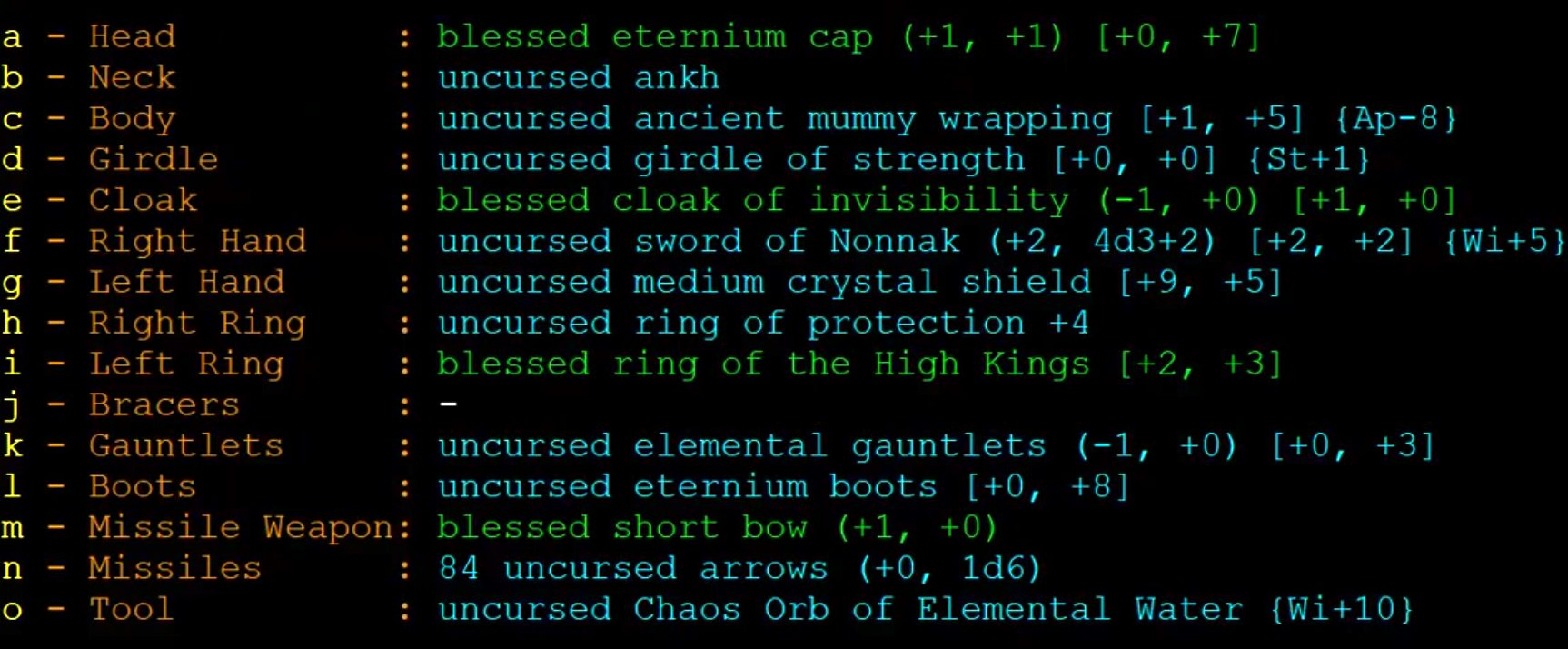

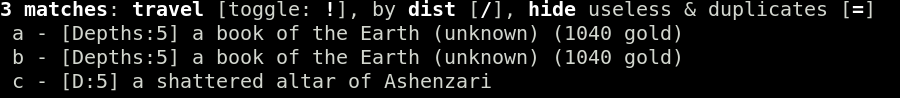

Roguelikes with backtracking, especially those that don’t play out in a linear dungeon, also add a greater amount of navigational overhead that developers will ideally optimize away through good QoL features. Again looking at DCSS, you have a way to quickly perform multifloor searches for locations of matching known objects in order to autotravel to them:

Auto-travel in DCSS to facilitate what would otherwise require players to have a much better memory, or take notes :)

Of course a roguelike player isn’t usually one to shy away from complexity, but the more you can streamline the process of getting to the fun decision-making parts of a game the better.

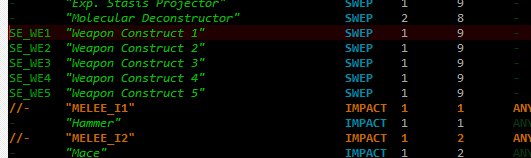

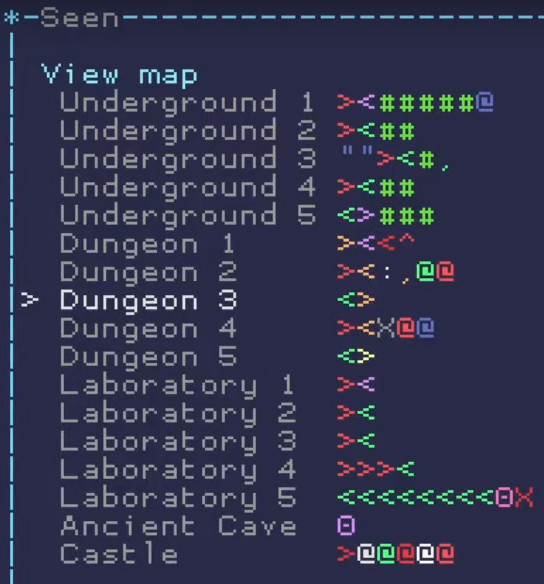

TGGW is a linear dungeon, but backtracking to visit certain dungeon features is quite useful at times, so it also includes a convenient map list accompanied by the characters for notable features at that depth--NPCs, stairs, teleporters, mechanical valves, terrain that might contain something… (there is also a key elsewhere on the UI)

Architecture

As we’ve seen there’s a good bit of design overhead for allowing backtracking, and this comes with additional architecture costs as well.

In terms of disk/memory footprint, in the modern day it’s no problem to store lots of old map data for potential reuse, though perhaps these considerations played some role in the decision behind always generating new maps in the earliest classics (Rogue/Moria). Naturally there’s also then the need to be able to reuse that data, which requires more supporting code.

There also might be a need for partial simulation of other maps, for example in order to enable methods to combat stair dancing, or add more realistic behavior, plus of course building any additional systems to support backtracking, be they mechanics-related or for the interface.

Basically: Doing backtracking right is going to require more work under the hood compared to just forgetting about the past :P

Addendum: Intramap Backtracking

So what I really wanted to cover in this article is backtracking to previous maps, since that’s usually what people tend to have questions about, or opinions on, in our community dev discussions. Backtracking in terms of “revisiting local areas on the same map,” however, doesn’t seem to get nearly as much discussion. Since it’s a somewhat related concept and worth taking into consideration during map design, I’ll add a few notes about it here.

Some amount of backtracking in this sense is inevitable for tactical reasons (retreeaat!!!), or even strategic ones (returning to face a previously discovered challenge after preparing, visiting a local stash, etc.), though absent of player-initiated reasons to backtrack, it’s nice to be able to leave it as a mostly optional part of dungeon navigation, especially in roguelikes with larger maps.

In other words, ideally the player isn’t experiencing too much “well I’ve fully explored this section of the map, time to trek all the way back to a junction to find other new areas.” The larger the map, the more relevant this issue becomes, so I’ve definitely taken this idea to heart given that Cogmind basically has the largest maps among non-open world roguelikes :P

For this reason I like to make sure there are enough looping paths providing alternative routes to reach different areas, meaning fewer dead ends. This helps cut down on backtracking and is more likely to offer new encounters rather than having to revisit cleared/now empty space, should the player choose to continue exploring forward. Retreading old ground is generally a boring part of a roguelike, and I prefer to keep the focus on exploration.

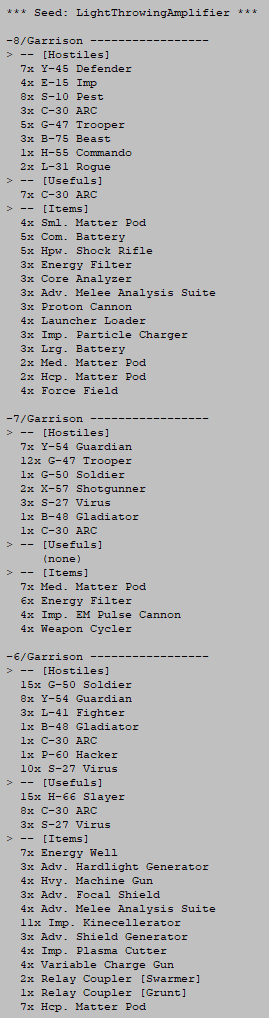

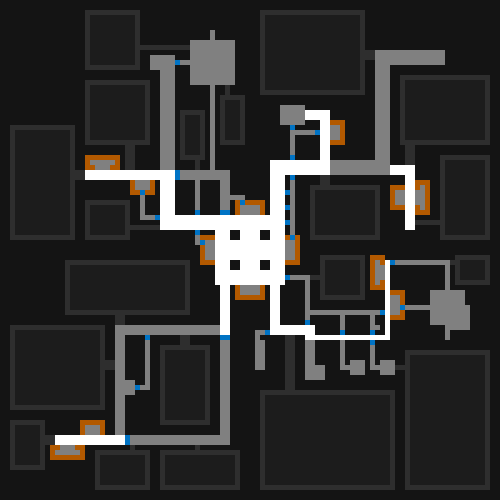

An old demonstration put together for one of my cave generation articles, with separate overlays showing both the general flow of the map and the loopable routes contained within, making it easier for the player to do more exploring than backtracking, even when traveling in a general direction (e.g. from one side of the map to the other).

As with freely backtracking to earlier maps, local backtracking can, however, be facilitated through QoL features to help mitigate the downsides.

Some roguelikes rely on autoexplore, which cuts down on the negative impact of empty space (both backwards and forwards!). Similar movement-enhancing features include “running” (commands to move in a single direction until an obstacle is hit), or even simply selecting a destination and automatically pathfinding to it, which is clearly pretty effective at unwinding a recent detour to return to a main path, or directly approach unexplored areas elsewhere.

Exploring a TGGW dungeon with the help of shift-modified movement keys, which will continue in a given direction until stopped/reach something interesting/see something dangerous, and even follow corridors.

Personally I feel that using the mouse to click some faraway spot to return from a dead end has a good chance of interrupting the flow of exploration in some roguelikes, turning the map into a series of disjointed encounters, the relative locations of which don’t even matter anymore. This topic actually comes up a lot with respect to game design and autoexplore being an unfortunate band-aid.

But we can sorta do something about that if we want to! Wandering threats are a big help (especially combined with interwoven looping layouts :D). That passage that was cleared earlier might not be so clear on the next visit.

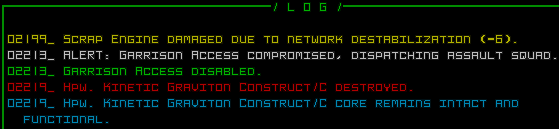

Cogmind has an easier time taking this to the extreme since it’s more of a living world than the typical roguelike, filled with lots of actors which means lots of potential encounters shifting around, sometimes across great distances. Some actors may leave the map, other new ones may come in… It’s a busy place, and the macro strategic environment combined with various clocks trying to push you forward mean that autoexplore is both wasteful and dangerous, which I think is a good sign in roguelike design.

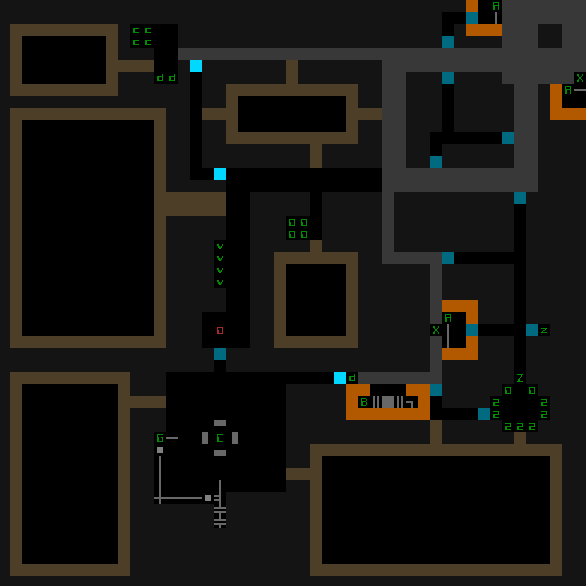

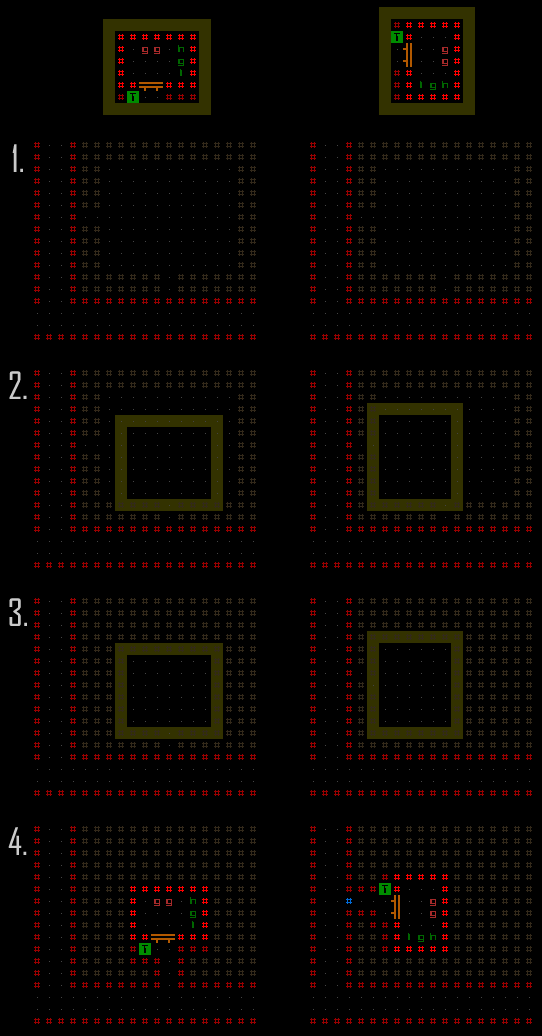

A bunch of actors (colored by category) doing their thing on one section of a map in Cogmind, and this is without player interference or other events, which might mix things up and lead to yet more variety.

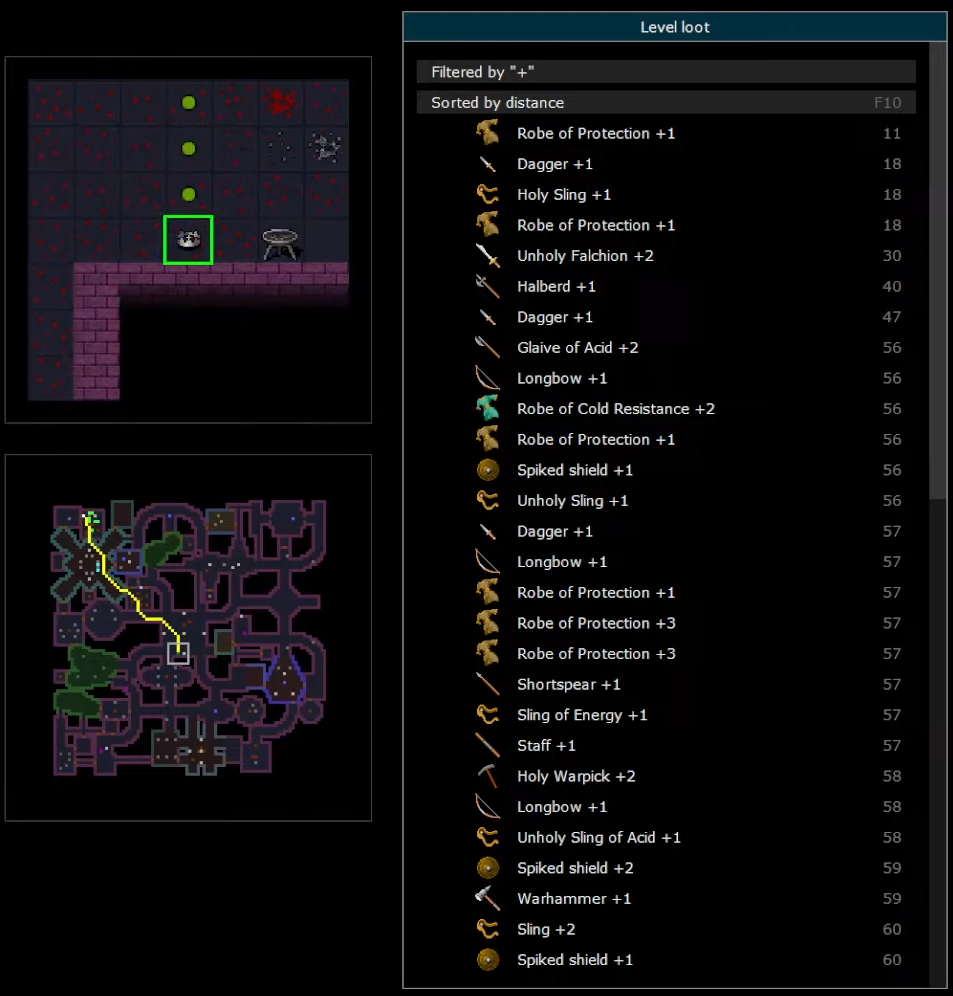

Earlier I mentioned QoL’s role in mitigating some of the potential negatives of backtracking, and yet another area for it to shine here is with features such as item searching and other memory aids.

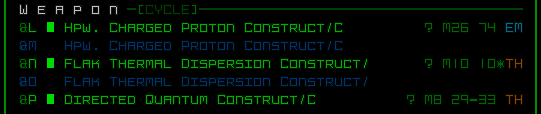

To that end I added item searching and filtering to Cogmind a couple years back, and it is pretty glorious when you need it.

In Cogmind filtering known items by name and/or other criteria, to highlight them on the map and path there.

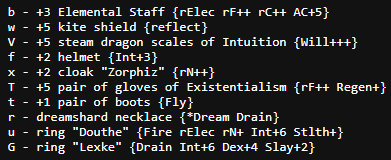

Zorbus’ item search and filter interface is similarly cool, a nice implementation that also includes a closeup of the selected item and its surroundings, as well as a path to it.

Zorbus item search UI in action.

Anyway, backtracking in the intramap sense is almost universally found to some degree or another in a roguelike. The real question is whether you’re going to allow players to visit old maps again, and get the most out of taking whichever approach you decide on :)