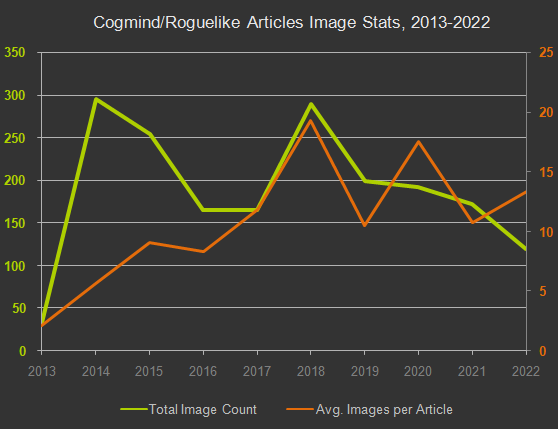

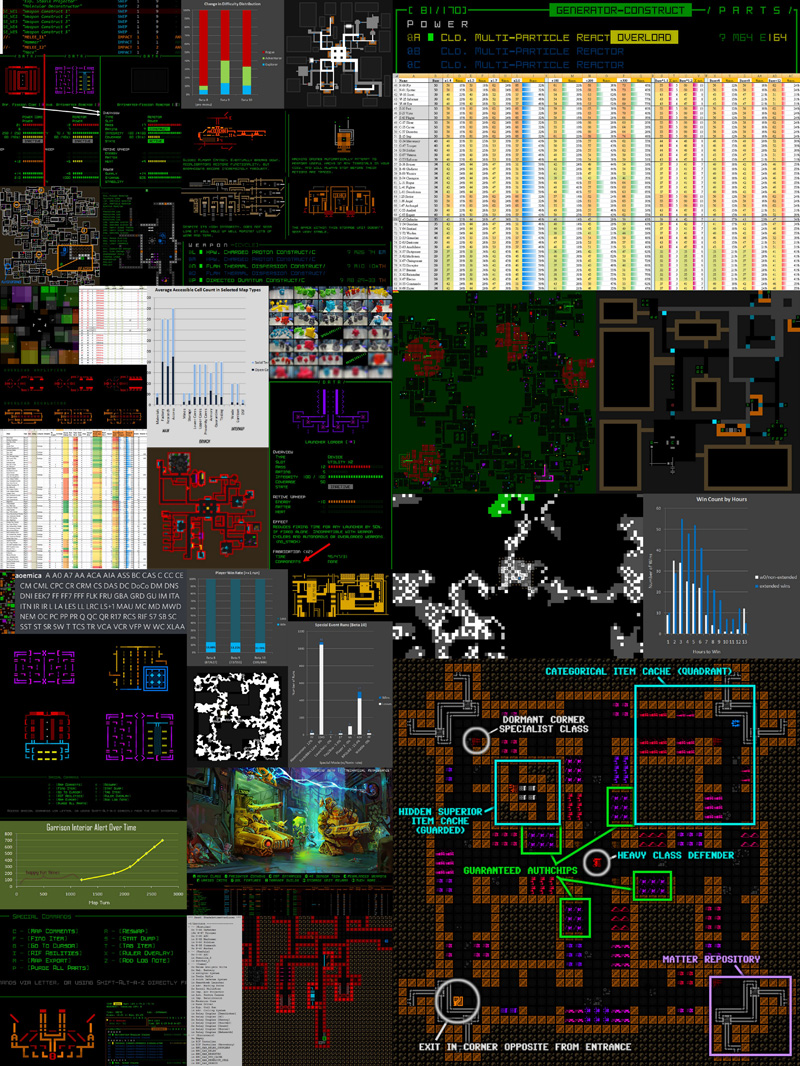

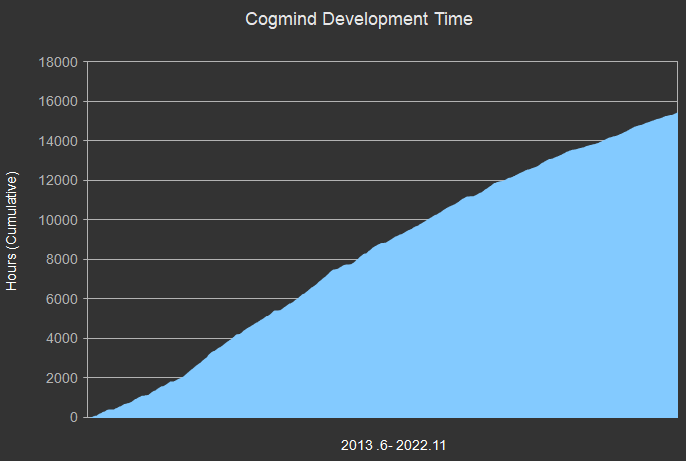

Beta 12 has released, and that means it’s once again time to examine player-submitted stats from the previous major release! Beta 11 was particularly special due to its sheer scope and secondary aim at rebalancing a number of fundamental mechanics, so unlike the usual shorter coverage of stats that I do over on the forums, let’s take a more comprehensive look at some relevant stats from Beta 11… (Beta 9 stats were the last I covered here on the blog.)

Overview

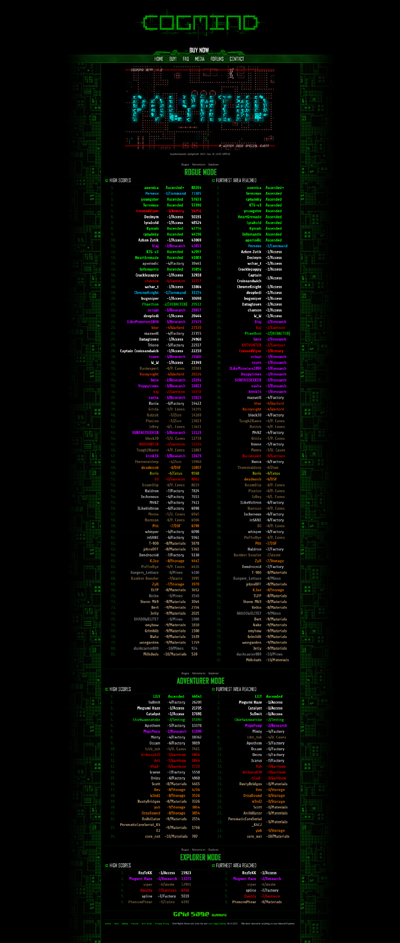

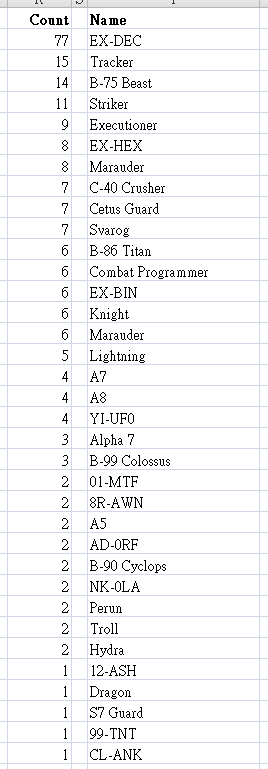

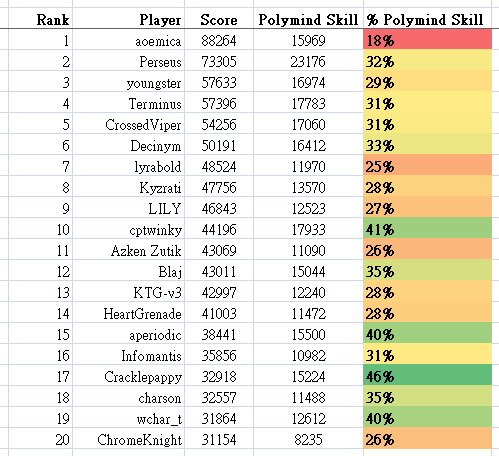

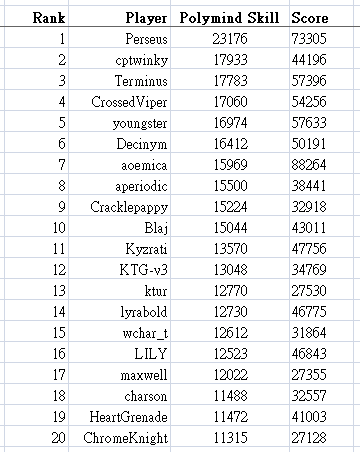

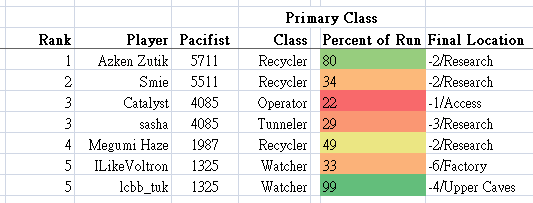

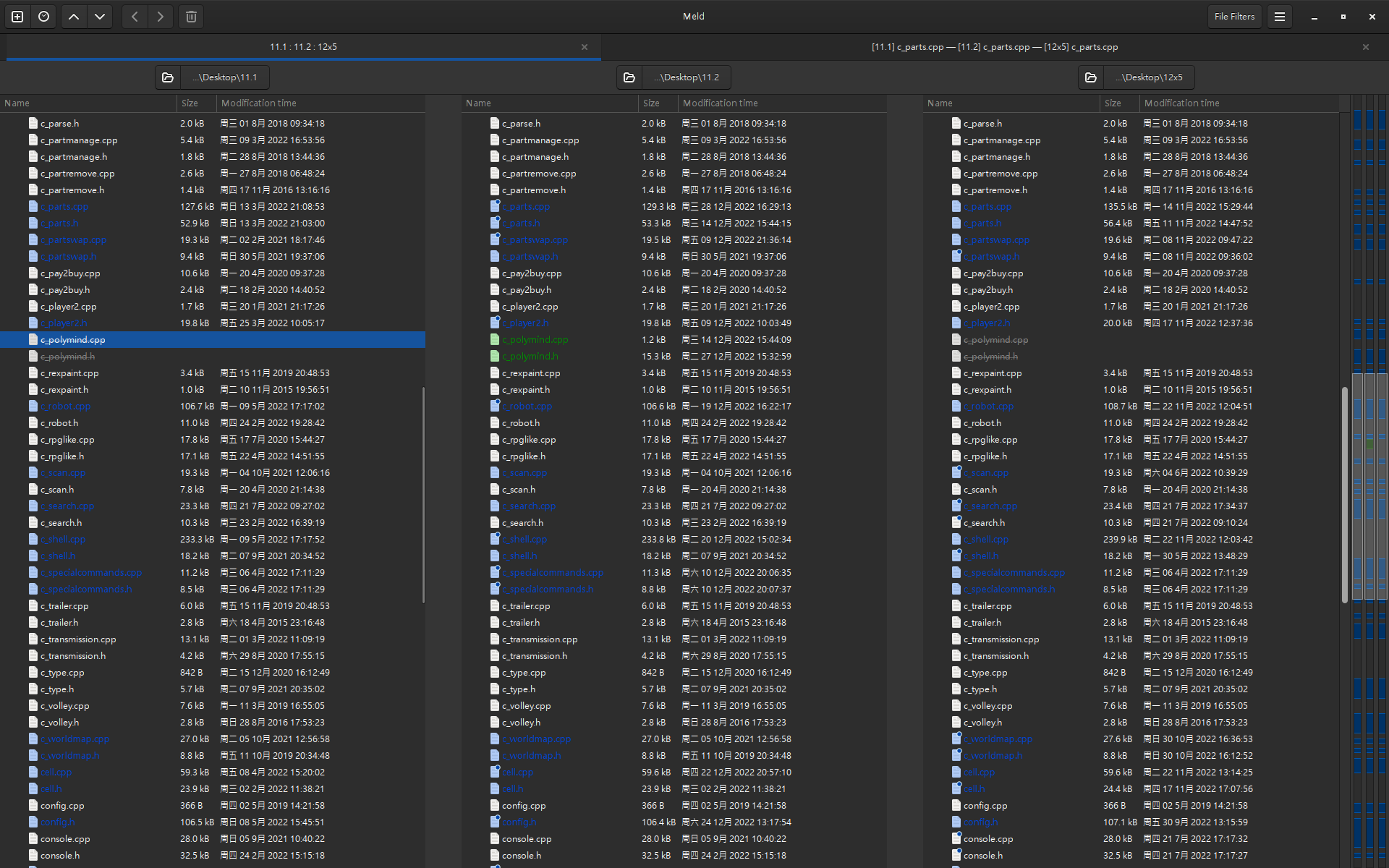

The data we’re examining spans the Beta 11~11.2 versions played from mid-March 2022 through the end of February this year, during which 935 unique players submitted a total of 11,207 runs. Of those, 895 (8%) runs are excluded here for being played in some special event mode, especially Polymind, for which I’ve already collected and shared stats in Part 2 of my Polymind design postmortem. Of the remaining runs, 10,062 had at least a score of 500 to be included in the leaderboards and general stats.

Patron activity was pretty significant throughout Beta 11 development, with 11 incremental prerelease versions to play, and since a big chunk of Cogmind player activity is by patrons (who also happen to be more likely to opt in to scoresheet submissions), technically an equally big chunk of our data can be traced to that group. That said, by default the stats below will ignore prerelease versions because 1) for our purposes we want to look at the final resulting “true” Beta 11, once it was no longer in flux, and 2) doing so also probably gives us a healthier cross-section of community data rather than allowing a small subset of players to significantly skew the results, as you’ll see in an example shortly.

In numbers, 2,997 runs were submitted from prerelease versions, accounting for 22% of the total (hence the real known run total was actually 14,204). I don’t really like the fact that Beta 11 ended up causing this large split, but that was a side effect of it being Cogmind’s longest beta cycle, and something we will generally be able to avoid going forward with somewhat more reasonably-sized releases and fewer prerelease versions.

Wins

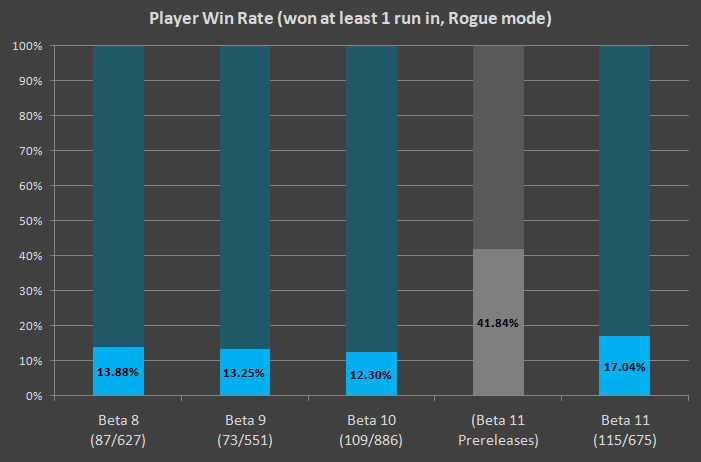

Beta 11 added new toys and mechanics, but also some significant new challenges (Heavies! Cargo convoys! …), so as with most releases it makes sense to look for any impact on the win rate, which has remained stable for a while now.

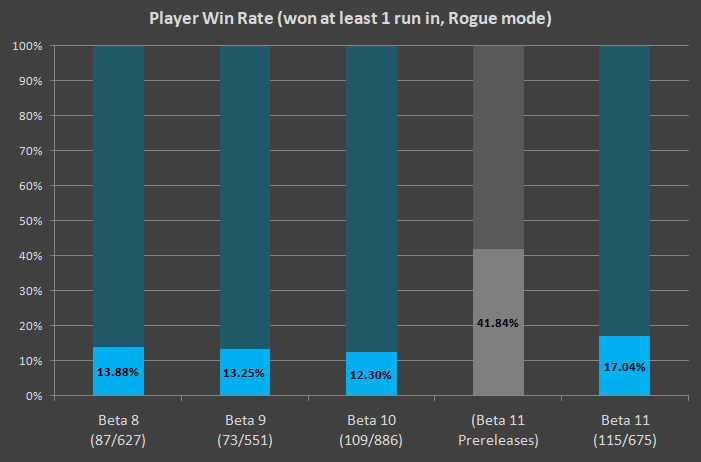

Reminder: For win stats I only examine runs in Rogue mode, since that’s what the difficulty is balanced around, and it’s the only mode that enforces permadeath.

The overall win rate in Beta 11 was 5.3%, so a bounce back up from 4.1% in Beta 10, but not quite up to the 5.7% in the version before that. So still generally hovering around 1 in 20 runs being a win. However, as usual my preferred measurement of win rate is to look at the percentage of players who reported at least one winning run in that version, so I appended the new data to our graph from last time.

Cogmind Player Win Rate (Beta 8~11, at least one win, Rogue mode)

Back to what I was saying earlier, notice the significant difference among those playing the prereleases, which tends to include many of Cogmind’s most experienced players.

Also interesting is the non-insignificant 33% uptick in win rate over the average from the three previous versions, which were relatively consistent. I can only speculate as to why this may be, but we can at least feel assured that Beta 11 is anything but a great increase in difficulty, and wait to see whether or how this value shifts in future versions. Is it an aberration? Or the new norm?

The most obvious potential reason, also reflected in the player count data, is that Cogmind had a smaller influx of new players during the previous version, leaving older players who are sticking around to get better and drive up the win rate.

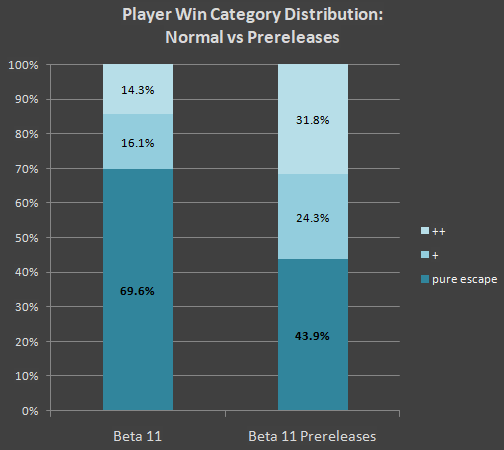

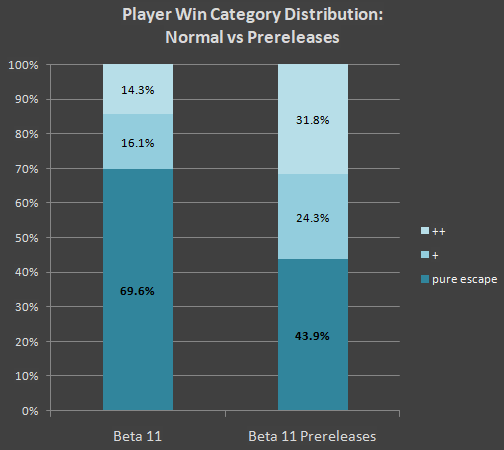

Another interesting graph, especially when comparing prerelease data vs the final version, is the distribution of win types. Here we find that about 30% of wins are extended-game wins that achieved boss kills. That’s quite a lot! Still, compare to the prerelease community, where most wins (56.1%) are killing bosses xD

Cogmind Beta 11 Player Win Category Distribution: Normal vs Prereleases

And the disparity there is not a potential side effect of smaller sample size--patrons alone reported 387 prerelease wins compared to the 454 of the entire public release group.

Difficulty

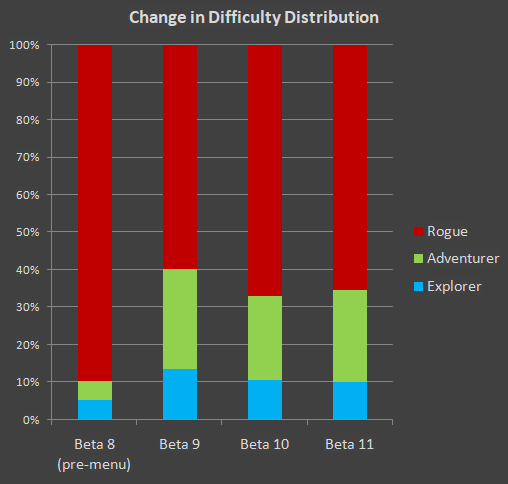

For the purposes of the remainder of this stat analysis, I’ll no longer be differentiating between difficulty modes--everyone’s included, though we can at least once again look at the ratio of players in each mode to see if there are any changes.

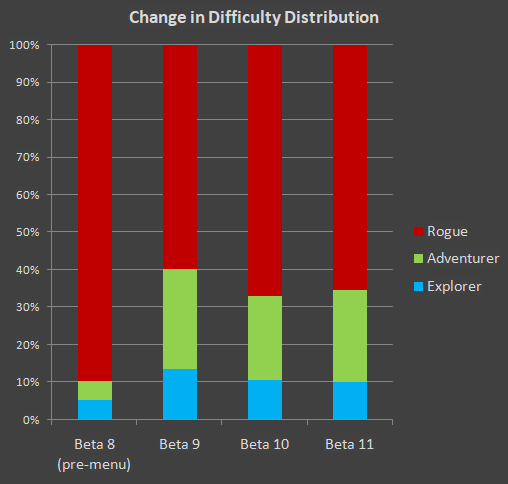

Cogmind Change in Difficulty Distribution (Beta 8~11)

It seems there’s no clear trend emerging, so we have found our normal distribution and probably don’t have to pay much attention to this value anymore. It was most interesting after the addition of the difficulty selection menu as the first thing new Cogmind players see ;)

Impacts of Rebalancing

Our next section here will take a look at pieces of data that might be interesting in light of changes to Cogmind’s existing mechanics, of which there were several major ones in Beta 11.

Storage

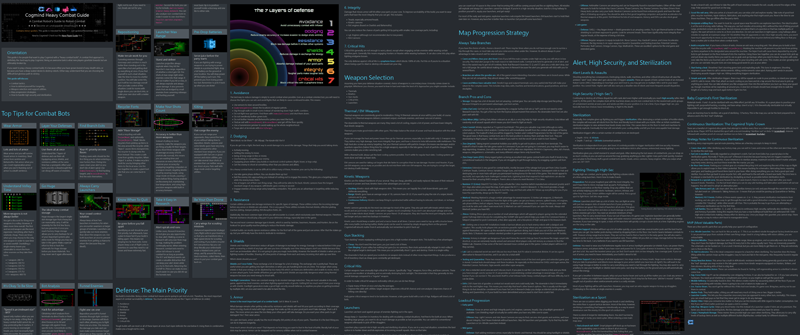

By far the biggest change was to storage units, removing their stackability to put a hard cap on inventory sizes while redesigning stats around that new reality as well as expanding the number of options. There are a lot of mechanical details and historical discussion/writing surrounding inventory management and various builds which I won’t rehash here, but anyway now that we have the latest data I wanted to compare changes to inventory capacities over time.

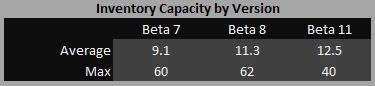

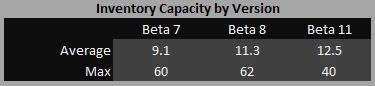

Cogmind Avg/Max Inventory Capacity by Version. The chart explicitly shows the Beta 7~8 transition, then skips two releases, because that was a fundamental transition during which the High-capacity Storage Unit was returned to the game after having been removed years before in 2016.

You can clearly see how the new hard cap comes into play, the maximum inventory size being limited to 40 slots, whereas in earlier versions the limit was whatever the player decided to devote their build to in terms of mass and utility slot requirements. Of interest here is that although outliers with massive inventories were clearly removed, the average capacity of a build increased due to the rebalance.

The rebalance included a larger base inventory size, an increase in how much each storage unit could hold, and a couple new storage options at the high end, essentially shrinking the portion of a build dedicated purely to inventory, apparently without having a negative impact on the average inventory size. Great.

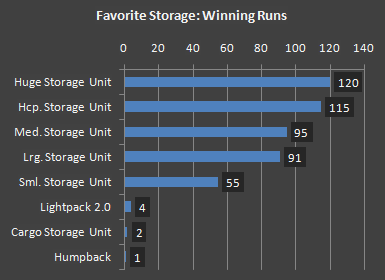

Another aspect I was curious about, given that we now have Cogmind’s widest-ever array of storage options, was which types of storage are the most popular, and among what kinds of players. For this data I relied on the “Favorite” item records in the scoresheet, which records the player’s most popular items of each type based on the number of turns they had it attached. Not an ideal reference basis for some use cases, but is simple and does mostly work for our purposes here.

Of course, technically our storage data will leave out a few players because the “Storage” type is shared with resource containers, but those generally spend most if not all of their time in inventory rather than attached, as opposed to storage units which are used continually throughout a run. Nonetheless, 3.9% of runs had a resource container as their favorite storage part. (Note that for these stats I’m only including runs that reached a depth of at least -6, because that gives players ample time to settle into their build and acquire the primary type of storage they want to use.)

4.4% of runs had no favorite storage type at all.

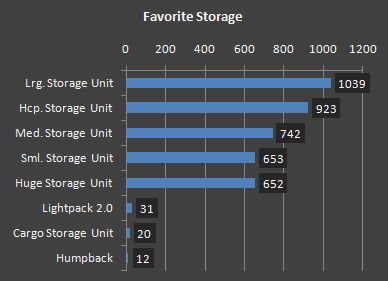

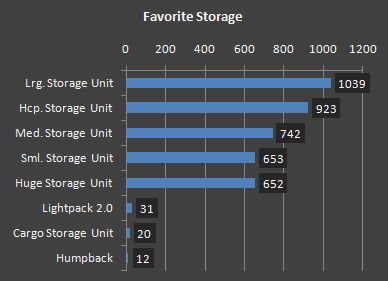

Moving on to our actual data, the winner of the favorite storage contest is… Large Storage Unit!

Cogmind Beta 11: Most popular storage type.

This wonderful middle-ground storage unit has a diverse range of applications, be it for combat builds that don’t need to go quite so heavy on inventory, or fast-movers that want to carry more. About a quarter of runs preferred to use it, and it also happens to be the storage unit used by Haulers, making it relatively accessible

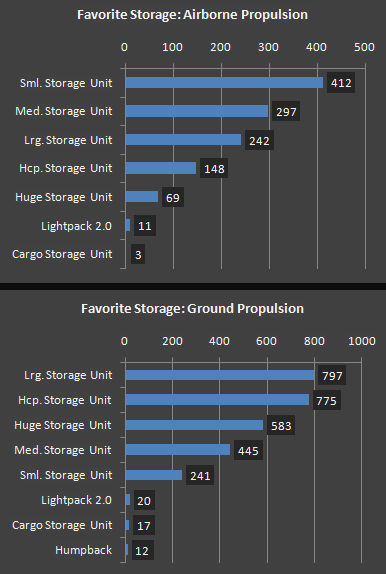

Surely though we’ll see a more telling difference in storage usage if we split runs into those using ground propulsion vs. airborne (hover/flight).

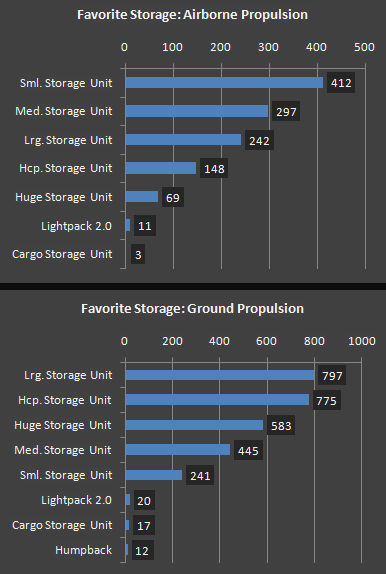

Cogmind Beta 11: Favorite storage type by propulsion category.

Not surprising that Small or Medium become the most popular if we’re talking about airborne builds, while heavier options are a more likely choice for ground-based builds. It appears that a decent number of airborne builds are still running Large (or even heavier options?!), but in many cases these values are probably not overlapping with the player’s time using an actual airborne build, but instead reflect a change of build at a different time. Cogmind is fluid, after all, with builds changing from time to time, and even transitioning from heavy combat to flight, or vice versa, depending on needs or strategy. So we can’t read too much into the outlying numbers as far as propulsion goes.

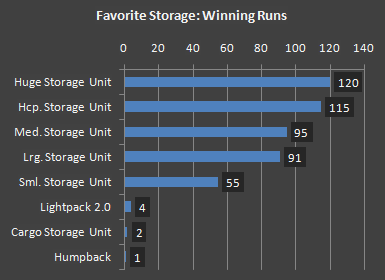

We can, however, take another look at the aggregate data, this time checking out what winning builds are going with…

Cogmind Beta 11: Favorite storage type among winning runs.

Huge has an interesting presence here at the top, especially when you go back and compare its place in the first favorite storage chart. It’s fairly clear that winning runs prefer larger inventories a lot of the time. Not extremely large, have you (we’re not seeing a bunch of Cargo and Humpbacks at the top), but having spare parts, or even whole other builds to transition into when the time is right, is good strategy if you can support it.

Speaking of Humpbacks, look at that Humpback win… They’re suboptimal storage by far (hard to use!), but “Pogmind” fabricated several as soon as possible (early Factory), including spares, and kept using them throughout the mid-game until downsizing their inventory to Huge in -4. The purpose was, I guess unsurprisingly, GUs :). It wasn’t the strategy referred to by the community as “garmy” (I’ll skip the spoilers), but they rather appropriately became a Hauler-Golem and used their extra inventory capacity to keep it going over many maps while still having room to store other gear.

I was also interested in the four wins that utilized Lightpack, by Momo, ktur, leiavoia, and Olga. Momo stole it from the Exiles, but didn’t start using it until the mid-game and then through to the end (an extended win relying on the new Exo build, which we’ll get to later). ktur stole the Lightpack as well (buncha thieves!) and used it as soon as they entered Factory, through to the end of their run in C. Olga borrowed it from the Exiles (so nice!) and used it almost immediately and through the entire run until -2/Research (possibly losing it) on what was a pretty quick run ending in a sprint to the surface. leiavoia also borrowed it (nice!) and used it on arriving in Factory and through the rest of the run to C.

Dominant Classes

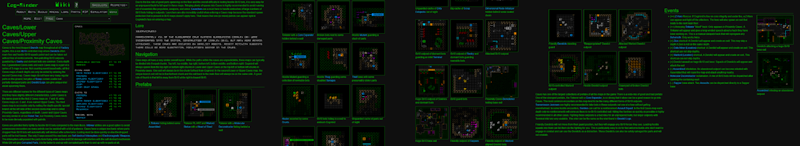

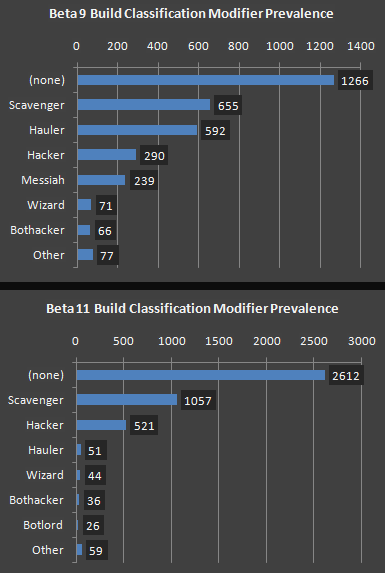

Speaking of Hauler-Golems, since build classifications were introduced back in Beta 9, that was one focus of the stats at the time, and I wanted to take a new look at whether there were any significant changes going into Beta 11.

For one, I would expect there to be fewer “Haulers” now, seeing as the redesign de-emphasized stacked inventories by concentrating all storage into a single part and leaving more room for other build-defining parts.

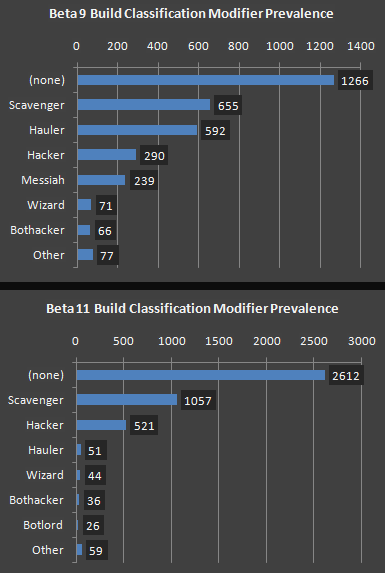

Comparing the most common build modifiers between Betas 9 and 11.

Indeed Haulers were appropriately reduced, although percentage-wise they were essentially converted to yet more “(none),” that is builds with no modifier at all. While it’d be nice to have more modifiers, this is okay since special modifiers are meant to be… special. (Already a couple new ones have been added for Beta 13.)

Another notable change: “Messiah” was bugged before, resulting in a much higher prevalence than intended. Clearly that got fixed :P (there was only one in Beta 11)

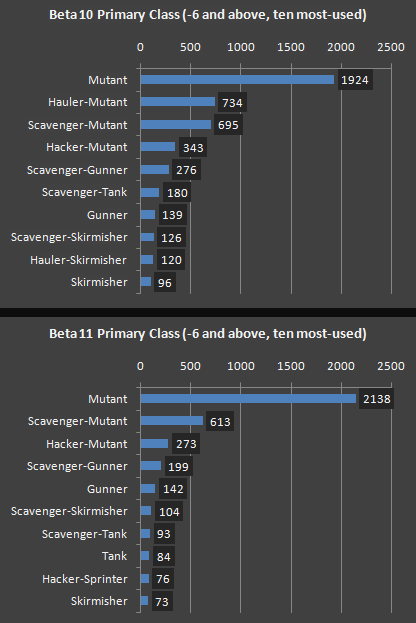

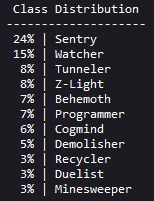

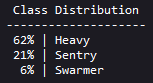

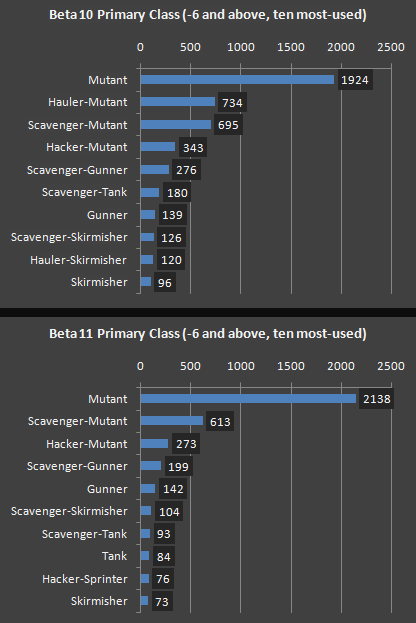

The variety of complete build classifications in Beta 11 remained relatively unchanged in Beta 11--75 compared to 76/67 in Betas 10/9, and there we also see Haulers slipping out of the top ten:

Comparing the most popular primary classes between Betas 10 and 11.

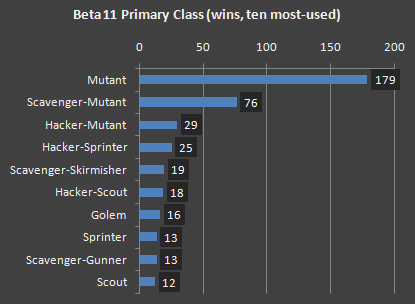

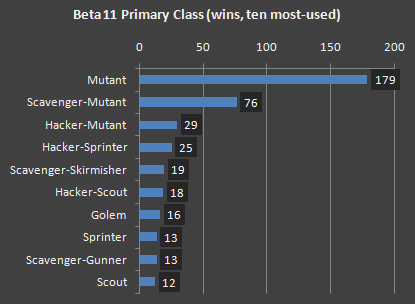

The top ten classes among only winning runs shows a somewhat greater number of unique builds:

The most-used primary class throughout winning runs.

Mutants and Scavenger-Mutants are still going to be the most common by far, since that really is what Cogmind tends to be.

Remember these graphs are only showing the class most prevalent throughout an entire run, so don’t really reflect the variety that happens from map to map. I didn’t analyze that particular data, which would take longer to extract, though I do wonder how it compares, even weighting for turn count in each map…

In the end this system is just for fun, and it does at least succeed at that (seeing players commenting on what kinds of builds they create, as defined by the game, is neat :D). While I’d like to define more base classes and modifiers, doing so in an effective manner requires quite a lot more work, including for example building a testing system that could read in player scoresheets for their peak builds and assign class names to allow for aggregate analysis and adjustments based on those results. Such a system would be further complicated by the fact that not quite all the data points factored into class names come from parts alone.

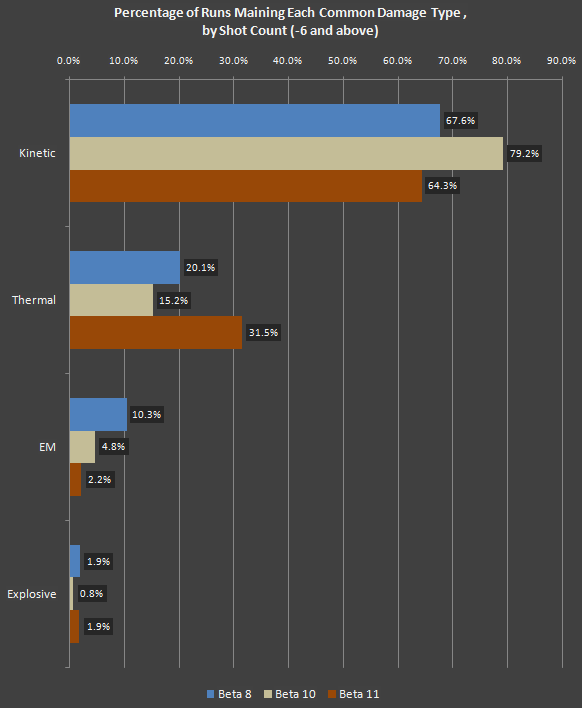

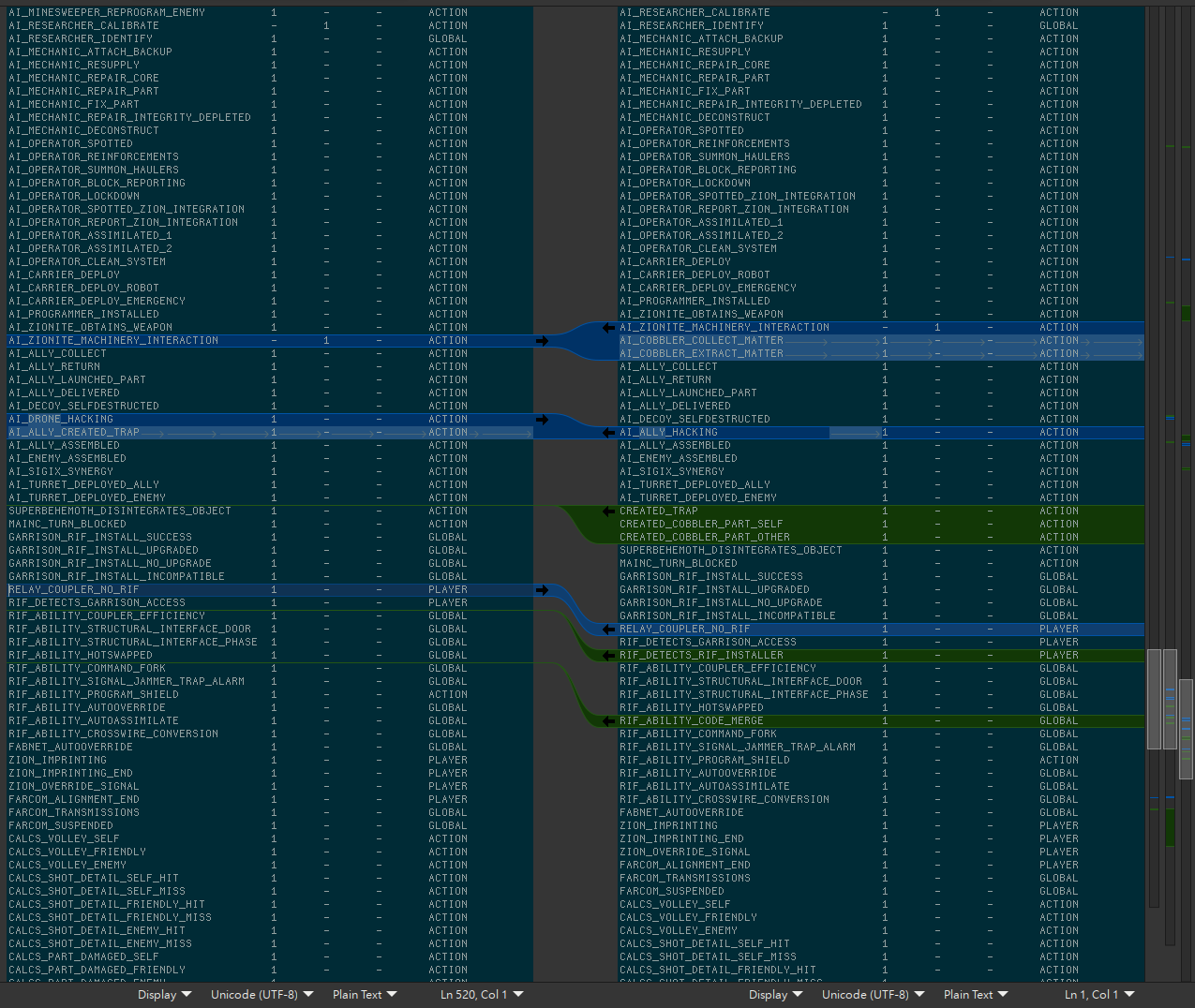

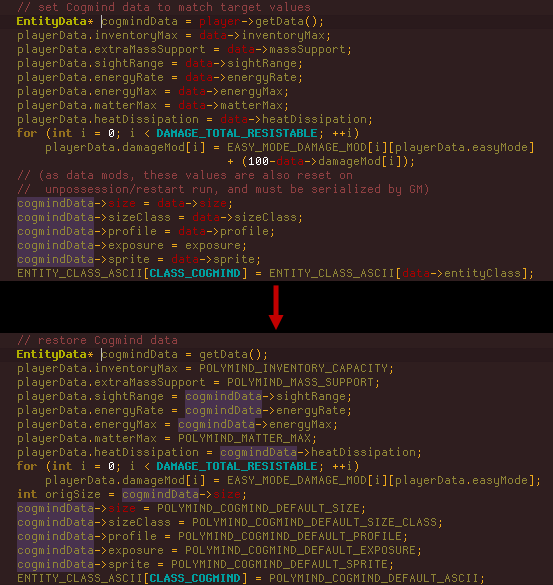

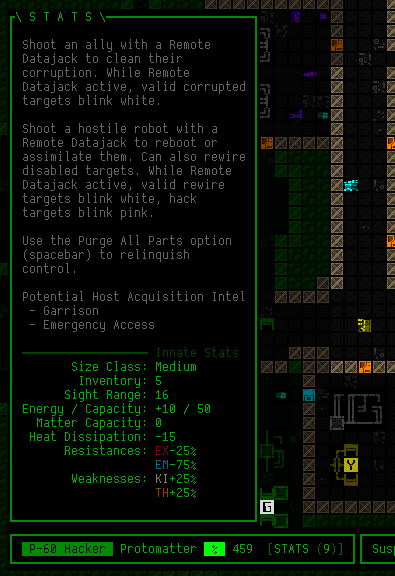

RIF/Bothacking

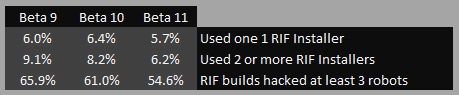

Another major mechanic to investigate in relation to storage changes is bothacking. Traditionally considered an inventory-heavy strategy by some players, did enforcing an inventory cap affect RIF adoption, or the effectiveness thereof?

Some of the massive inventories seen used by players in pre-Beta 11 builds were indeed put together specifically to carry a huge number of spare Relay Couplers, though the assumption was that by reducing utility allocation towards storage units, more of those couplers could instead be directly attached to provide active benefits and flexibility, as opposed to having more limited options at once.

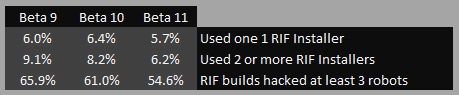

Some core RIF stats for the last several Cogmind releases.

According to the data, somewhat fewer runs started the RIF journey by using any installer, and there was a greater drop in the number of runs that continued that journey towards maximum RIFness. Technically the latter can also be attributed to players adopting a low-RIF strategy that only wants to use a single installer, combining the benefits with other strategies, so I wouldn’t read much into it. Same with the continued drop in RIF builds that hacked at least 3 robots, which also fell but actually by a smaller percentage.

Comparing the average number of different Relay Coupler types attached at once, as expected that did increase from 2.7 in Beta 10 to 3.0. A handful of players in Beta 11 were often running around with ten or more couplers attached at once! The average total value of couplers attached at once in Beta 11 was 78, also an increase to Beta 10’s 75.

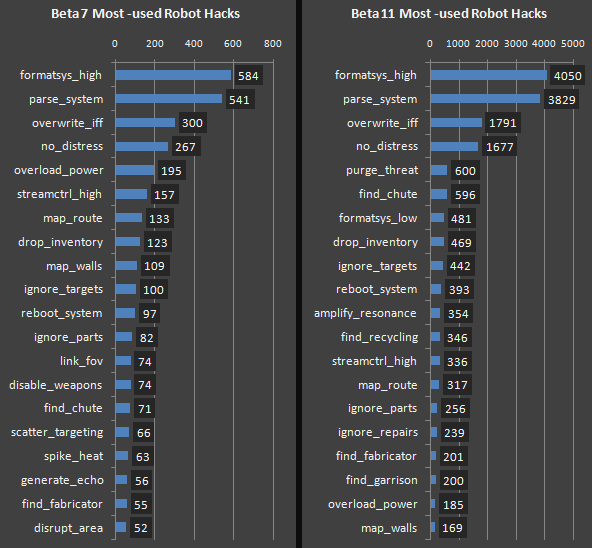

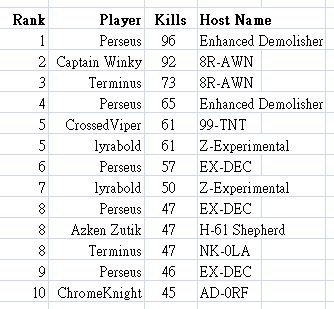

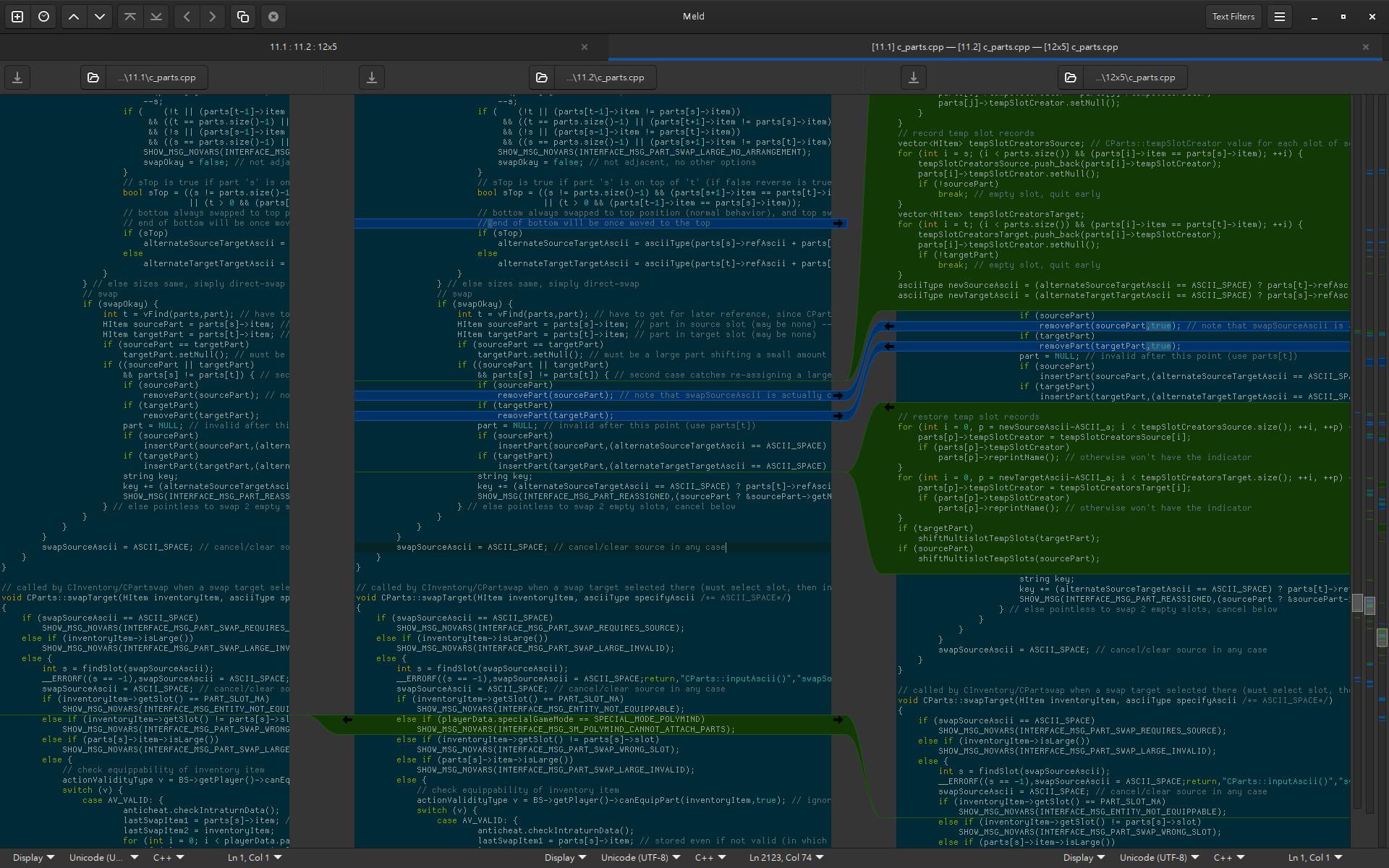

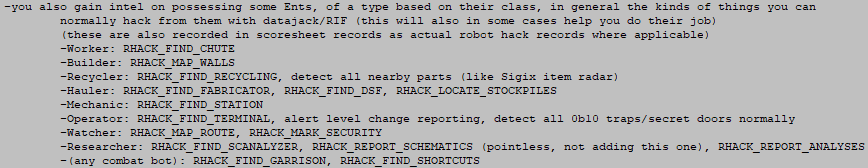

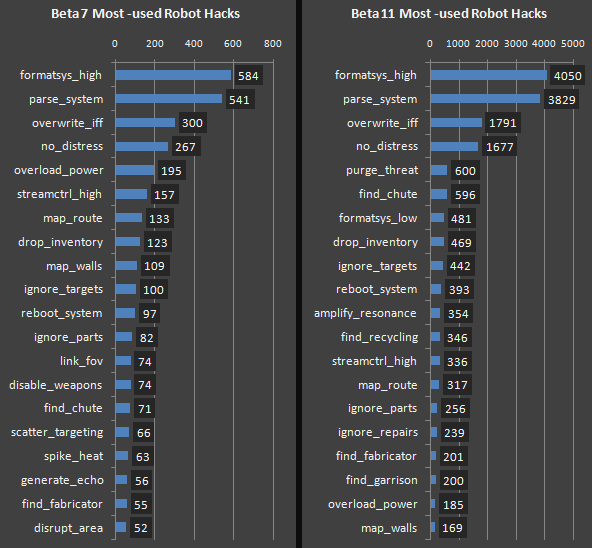

Way back for the Beta 7 stats we looked at the relative popularity of different robot hacks, so while we’re at it let’s see what’s changed since.

Comparing the most popular bothacks from Betas 7 to 11.

Ignoring raw numbers since there were a lot more Beta 11 runs, we can still see that the top four hacks remain unchanged, and…

- purge_threat, while #5 in Beta 11, didn’t even make the top 20 in Beta 7 o_O

- overload_power dropped significantly, functionally replaced by the newer amplify_resonance in many situations

- find_chute, which?doesn’t even require RIF at all, is definitely growing on people, helping avoid those pesky chutes when you don’t want to get sucked away (or finding one when you do want to)

- formatsys_low has gotten lots more popular (more green bot manipulation! smart RIFfers!)

From both the data, and what I’ve seen anecdotally, RIF is alive and well.

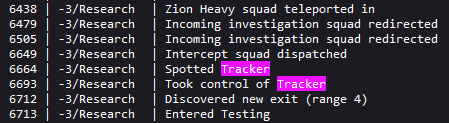

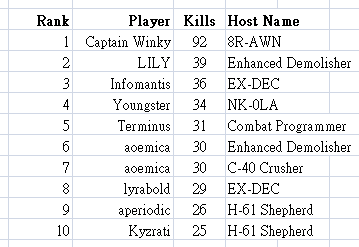

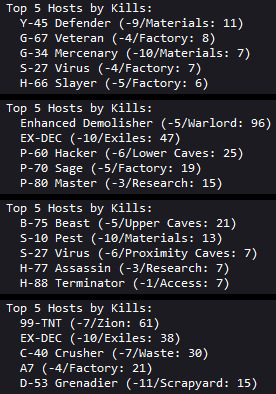

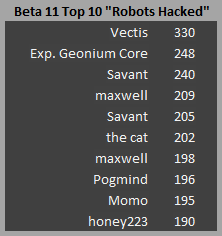

Our Top 10 bothackers from Beta 11, ranked by the number of different robots hacked in a single run.

Propulsion!

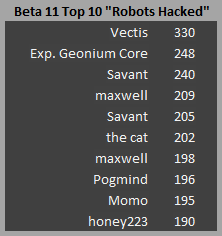

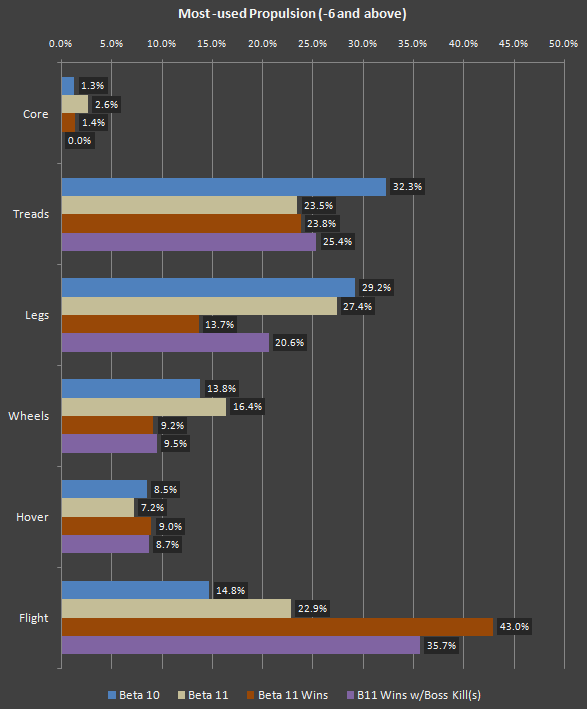

Propulsion underwent some significant rebalancing, so I’m sure we’re all curious to see if that had a noticeable impact on larger trends. From what I see… I don’t think so? Certainly a portion of strategies and builds were affected, with some older approaches fading from favor and newer ones joining the mix, but in terms of the spread of propulsion types that are being used for the majority of a given run, there hasn’t been any huge paradigm shift.

Comparing primary propulsion type preferences between Betas 10 and 11.

To calculate this I looked only at runs that made it to at least -6, and determined the primary propulsion type of a run to be that which was used to move the most spaces. Crude, but at least somewhat representative :P

Without close examination of individual scoresheets (technically there’s enough supporting info inside…) we can’t easily algorithmically account for players who are forced to switch propulsion types, or temporarily use one type of propulsion when the real goal, and most important parts of that run, instead rely on a different type.

Freely available multislot treads being much less common in the late game could easily have contributed to the drop in that figure, but sometimes it’s also just a case of having more of a certain type of player during a given Beta, especially seeing as a lot of players seem to like sticking to either ground or airborne propulsion for the majority of their runs. They are very different strategies and gameplay styles after all, and preferences differ.

Regardless of whether extracting each run’s most-used propulsion and tallying those, or taking the total spaces moved for each type of prop from all included runs, the end result is about the same: Airborne propulsion is used about a quarter to one-third of the time.

Note that in both calculations, airborne prop is always skewed down a bit from how often it is normally used, since it is not available from the very beginning, and is challenging to main before leaving Materials, so we could get an even more accurate representation by excluding those depths.

But it’s also telling to look at full-length runs that went on to win, which I included in that graph. Flight definitely takes the lead there, being the safest way to earn the simpler win types, and even good at more safely gathering the pieces necessary to put together the best build upon reaching (or nearing) extended game areas for… bigger confrontations.

The least commonly used propulsion is still hover, being harder to build around and maintain, but also arguably the best if you can use it (kind of the expert prop among experts). Wheels are good but don’t have the same longevity as other ground prop, so are used for a smaller set of builds, or for some people primarily in emergencies.

Damage Types

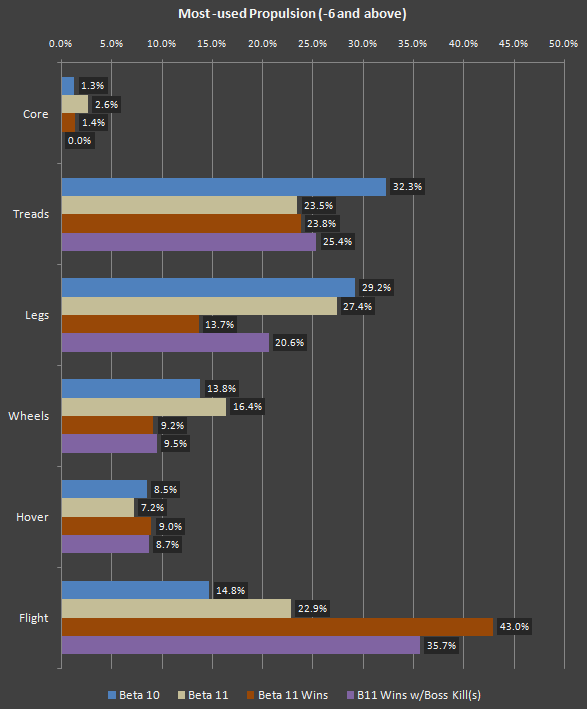

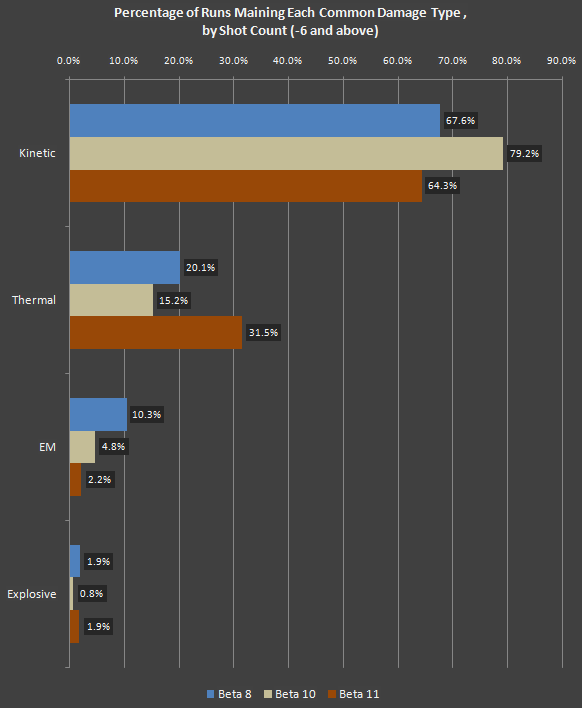

Changes to some common damage types have expectedly had a noticeable impact on usage preferences, for which like propulsion I analyzed by checking runs to at least -6, counting the percentage of those runs that fired more shots from a given weapon type than any other.

Comparing damage type preferences from Betas 8, 10, and 11.

Thermal use shows a sizeable increase after buffing that category in Beta 11, primarily at the expensive of Kinetic weapons, the other of the two most-commonly found (and used) damage types.

Electromagnetic weapons were nerfed going into Beta 10, cutting their usage in half, and again in Beta 11, cutting it in half again :P. While it’s worth noting that strong EM builds can take fewer shots to kill most targets, meaning shot count (or even damage totals) don’t offer a great comparison to other damage types, relative usage from version to version is clearly down. There’s room for that to bounce back up a good bit in a future update surrounding corruption mechanics, but we’ll see if and when that comes to pass… For now I’m good with it where it is, being still pretty effective in combination with the right build and strategies, but no longer an easy approach for any build that wants to just plug it in.

EX damage was added to the graph purely for completion, as one of the common damage types, though being situational it will always remain low compared to the others on a graph like this. But if you think about it, 1.9% in Beta 11 means nearly 1 in 50 runs is someone going ham with explosives and making it to at least -6 like that :P

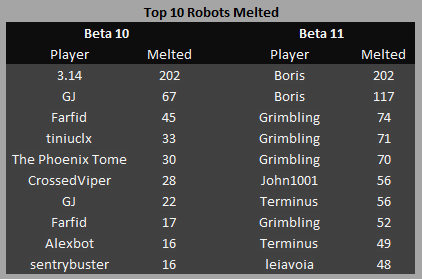

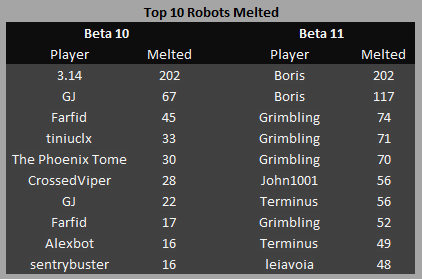

With regard to the increase in thermal weapon use, we also see a marked increase in robots melted in Beta 11 due to thermal transfer.

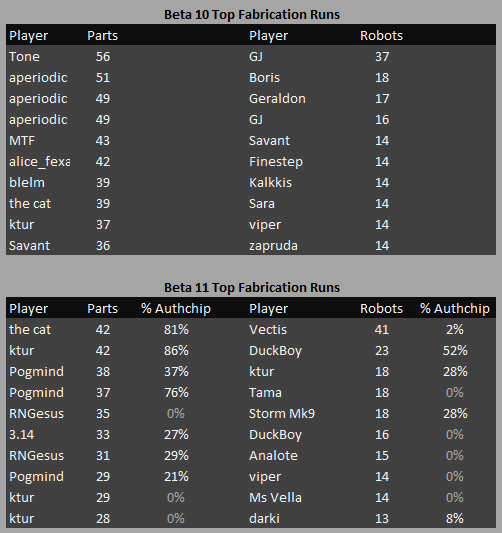

Robot melting leaderboards from Betas 10 and 11. You really had to work at it before, but melting robots is now a more common side effect of thermal volleys, not to mention the group of new weapons specifically aimed at increasing melt potential.

Corruption

One of the big changes to EM damage in Beta 11 was of course the potential to corrupt the victim’s salvage, causing some amount of system corruption when attached. This may cause players to shy away from corrupting targets with desirable salvage, or avoid attaching quite as much of that salvage as they would before. Still, sometimes you just have to put on that extra corrupted part to survive, or maybe just don’t care :)

Due to the changes we’d expect the average system corruption to increase in Beta 11, and indeed it did, up from 2.6% to 3.3%. Also note that even if EM weapon use is down overall, targets can still become corrupted in other ways.

The number of actual deaths to system corruption remained unchanged, however--that’ll always be quite rare since other contributing factors tend to kick in long before that :P

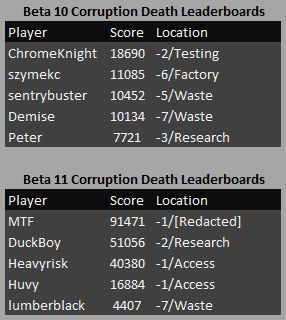

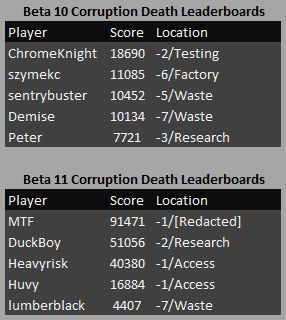

System corruption death “leaderboards.” There were five recorded in each of the last Betas, accounting for 0.05% of Beta 11 runs, and 0.04% in Beta 10.

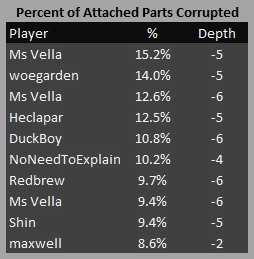

The average number of corrupted parts attached in runs reaching at least -6 was 1.4, so not exactly high, accounting for only 0.6% (~1/200) of all attached parts. I found it amusing that the absolute highest amount of total corruption from attaching corrupted parts was 190 by “deadnoob,” who attached 31 corrupted parts (6.5% of their total), and made it to -1/Access in that run.

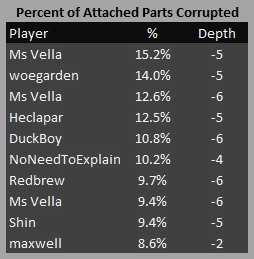

That run didn’t even make the top ten when comparing across all Beta 11 runs the highest percentage of attached parts that were corrupted:

Beta 11 runs attaching the highest percentage of corrupted parts--up around 10% or more is quite a lot! (incidentally I noticed woegarden on that list, who happens to have recently released an album inspired by Cogmind!)

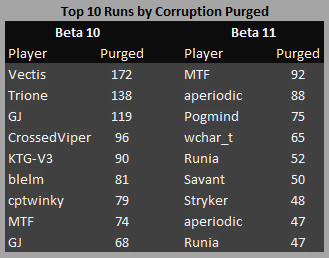

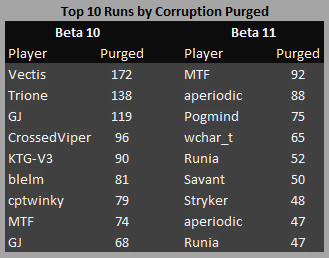

Following the readjustment of corruption-related utilities for Beta 11, the amount of corruption purged has come down somewhat, most significantly a result of capping the amount of corruption individual utilities can purge. Among runs reaching at least -6, the average amount of corruption purged in Beta 10 was 3.23%, falling to 3.04% in Beta 11. The same trend is reflected in the top corruption-purging runs of each release:

Comparing the top 10 runs by total corruption purged in Betas 10 and 11.

Since the community is split on how much corruption really matters, the types of players playing each version may also impact whether and how often to purge corruption (and you see a lot of different names in the above graph because we did indeed have different players more likely to be playing one or the other), though I’m sure the main reason behind the disparity is that it’s no longer possible to wait in certain areas practically indefinitely with a single utility normally stashed away in one’s inventory to clear corruption. The fact that purging dropped but is still decently high, even with a cap, at least shows that the relevant utilities are common enough to be of help, and getting use.

Next time we’ll have to look at how many people were actually using the new corruption screens. They are better at preventing greater amounts of corruption, and I know some players used them and the data was reported in scoresheets, but the analysis program I was using left them out and I didn’t discover until too late to include them here xD

New Content and Mechanics

How about that new content!

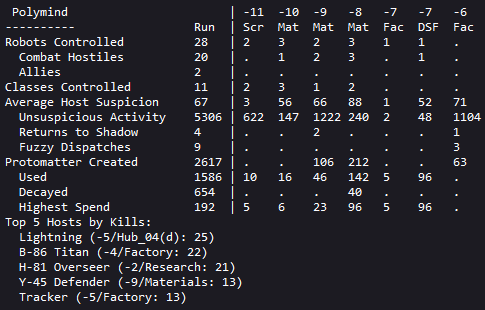

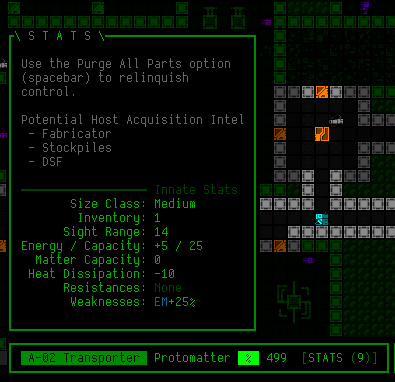

DSFs

Distributed Storage Facilities became places you can actually visit in Beta 11, so how many people have been doing that? 1,056 runs (10.5%) visited at least one DSF. Of those, 138 (13.1%) visited more than one, with Jezoensis setting a record by entering 4 in a single run (the theoretical maximum number that can be visited is five, though the process to enter any more than three is already rather convoluted).

Since the entrances tend to be locked early on, I was curious about how much time players tend to spend in Factory/Research maps prior to entering a DSF: Apparently the average number of turns is 92. Out of 1,210 total DSF visits, half were within 53 turns, and a quarter were within 17 turns.

The absolute longest anyone ever spent on a map before successfully entering a DSF was a whopping 1,538 turns, by yub. They weren’t just sitting around, and they were indeed spotted a little, but it looks like they were jamming at the time, which is the easiest way to keep DSFs accessible for so long--just jam all comers :)

The number of runs that ended in a DSF: 155 (14.7% of those that entered). 42.6% of those died to the sterilization system. Oops. But this was also the first release to include DSFs, so of course it’s a learning period during which you have more people entering for the first time just to see what’s in there, and not necessarily knowing what to expect.

Critical Strikes

Beta 11 significantly expanded Cogmind’s array of critical strike effects, but as they’re more an expected occasional side effect of damage types (which we already covered) and we have nothing to compare to since they’re new, I don’t have much to look at here.

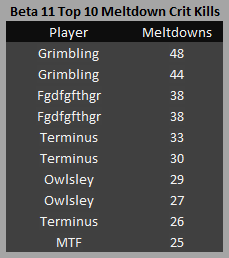

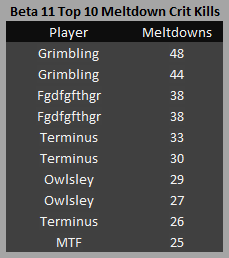

One of the more extreme effects, meltdown, is also on the rarer side for a common damage type, appearing with pretty low base chances on some thermal cannons, so I was curious to see how effective that is for some players and put together a chart for that.

Beta 11 top 10 meltdown critical strike kill counts. Getting several dozen outright meltdowns across a run is a pretty neat reward. I’ve seen screenshots of one-shotting tough Behemoths with builds that do this, which has gotta feel good :)

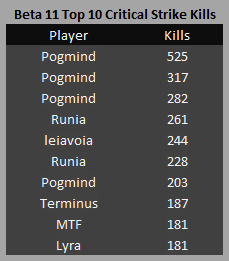

Overall, crit-focused builds seem as alive as ever in Beta 11:

Beta 11 Top 10 critical strike kill counts. Pogmind (nogimagogi from Discord) is clearly a fan of this strategy :P

Traps

Traps have always been an increasingly useful supporting mechanic, and Beta 11 further upped their potential by allowing them to be stored within Trap Extractors, so we’d expect to see a greater emphasis on trap use in Beta 11. The data supports that assumption, showing that on average nearly four times as many traps were extracted in Beta 11 (0.165) compared to Beta 10 (0.046).

2.6% of Beta 11 runs actually found and used a Trap Extractor at all, compared to only 0.7% in Beta 10. Interestingly, the average number of extracted traps was almost identical between the two releases, and the average install count was actually 28% higher back in Beta 10, though this is due to outliers and usage of other non-standard derelict tech.

If we instead compare the top 20 players by total traps extracted, i.e. those people leaning heavily into use of the new Trap Extractor mechanics, we instead see both a 29% version-over-version increase in extraction count, and 43% increase in traps installed among that group.

It’s definitely a become a pretty strong approach in its own right, and anecdotally the advent of extractors holding traps separately has indeed increased the prevalence of new trapping strategies vs. dangerous or high-value targets, rather than using up traps ASAP to free up inventory space.

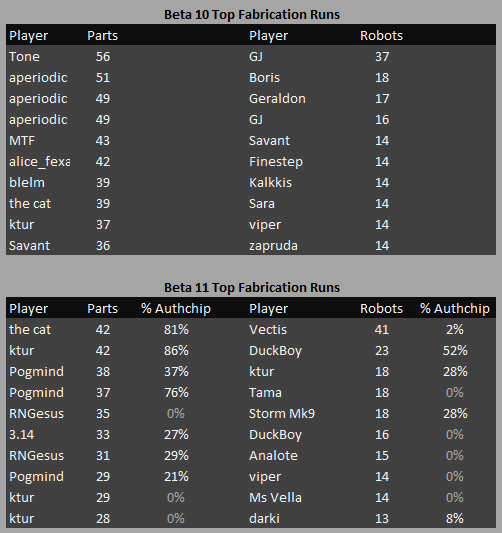

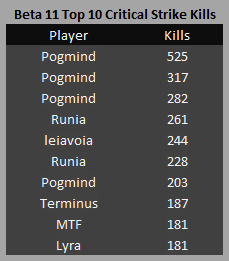

Fabrication

Beta 11 overhauled the fabrication process, and while some players were worried this would ruin the ability to create builds via those means, I don’t think that’s turned out to be the case. From what I’ve seen so far, everyone basically just needs to learn and grow accustomed to using the new systems. Fabrication-centric strategies are emerging as before.

The numbers are still down, though.

Looking only at runs that reached at least -6 (since there aren’t any Fabricators until reaching Factory), 40.9% built at least one part in Beta 11, versus 54.2% in Beta 10. Players built an average of 1.6 parts in Beta 11 runs vs. 2.5 in Beta 10.

There was a lesser impact on robot fabrication, most likely due to the less specific categorization of robot Authchips combined with the fact that fewer people tend to fabricate allies in the first place. 13.3% of runs to -6 built at least one robot in Beta 11, versus 14.5% in Beta 10. Players built an average of 0.44 robots in Beta 11 runs vs. 0.48* in Beta 10.

1,187 runs (11.8%) carried at least one Authchip, and 60.0% of those runs actually used one to build something, which doesn’t seem too bad. Duckboy carried the most Authchips at once (13!) and used them to build a giant army :D

Comparing the top fabrication runs from Betas 10 and 11, we can see that despite the reduction in parts produced, dedicated players are still making good use of Fabricators with or even without heavy use of Authchips (depends on strategy!).

Top fabrication runs in Cogmind Betas 10 and 11, including parts and robots, and showing what percentage of Beta 11 fabrications were completed with help from Authchips.

Fabnet

This section and the remainder of the stats will be covering a few spoilery bits of Cogmind, so feel free to bow out now if you’re not ready to read more about fabnets, SR targets, and the new end-game Exo build.

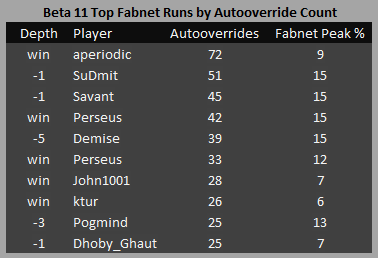

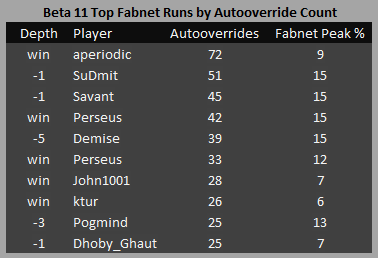

So we have a new strategy for abusing Fabricators to interfere with Complex 0b10 operation, which doubles as an alternative way of making friends. Obviously I’d like to know just how much it’s been getting used, and it turns out quite a lot!

7.9% of all runs that made it to at least -6 reported using some amount of fabnet (-6 because this feature doesn’t even kick in until then), and 15 runs hit the fabnet cap (15%) at least once.

Beta 11 top 10 fabnet runs. Look at that 72-override win by aperiodic!

Having been just introduced in Beta 11, I’d like to keep an eye on this feature next time to see if it picks up as more people discover it, or falls by the wayside.

SR Targets

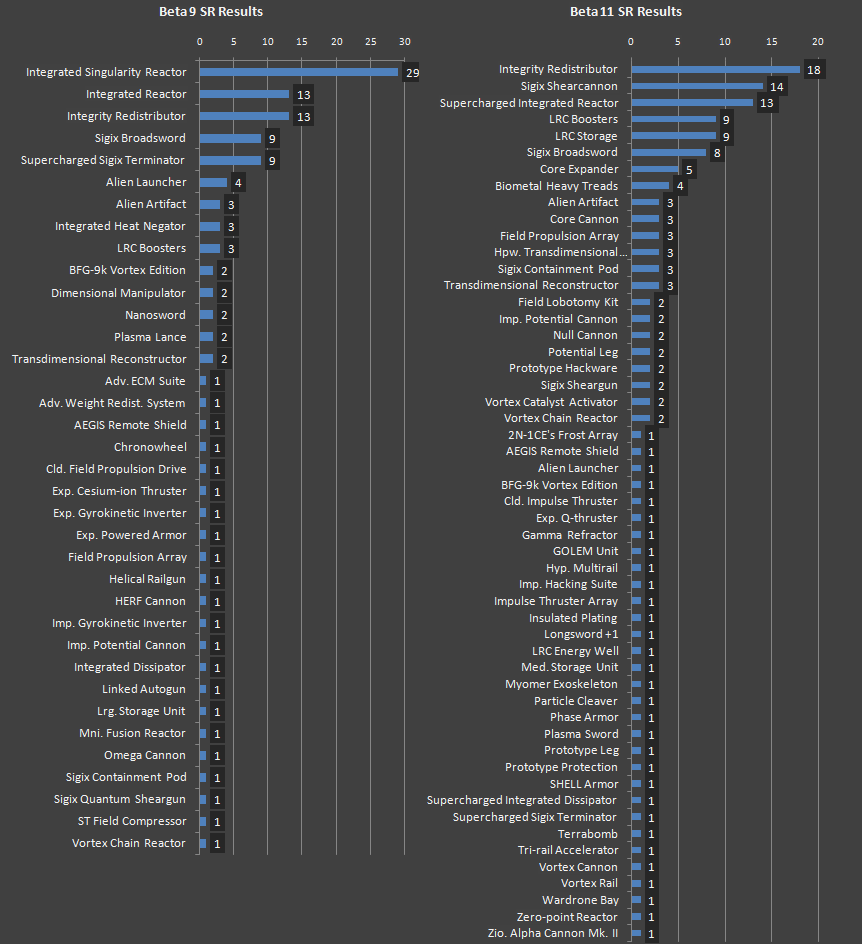

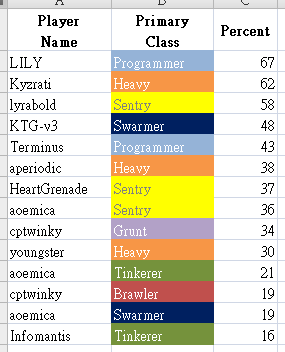

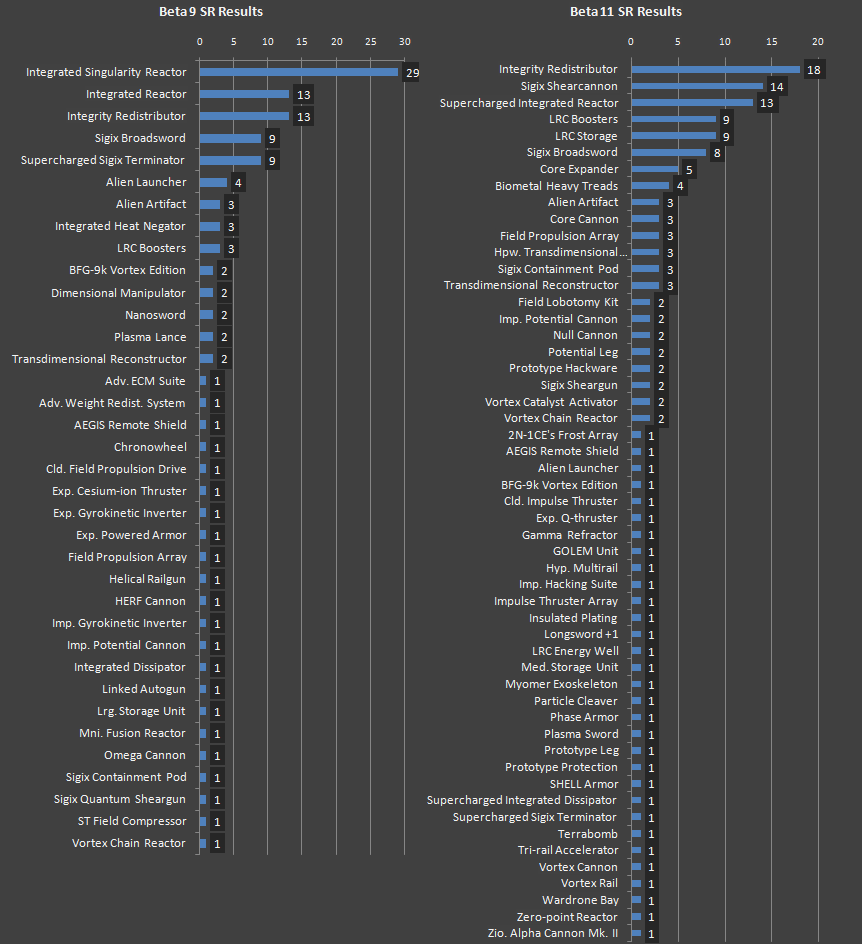

Several changes to various artifacts, as well as the addition of some new ones, have occurred since the last replication check in Beta 9, so I’d like to see if there has been any meaningful change in SR targets since then.

Below I’m reposing the old Beta 9 graph alongside the new Beta 11 data. Normally I would be most interested in, and only share, the top uses, but specifically with the replicator, since it’s so unique, it can be fun to see what individuals are doing with it so we can imagine what they were up to at the time (aoemica specifically didn’t need it on one run--the Med. Storage Unit is their work).

Comparing SR results between Betas 9 and 11 (open at full size for easier reading).

This time around we have 53 different SR targets vs. 36 last time, a 47% increase, compared to a lesser 23% increase in the absolute number of replications, so the variety of uses did in fact increase.

One of the biggest catalysts here was the ISR replication nerf to make it create an enhanced version of the original artifact rather than purely duplicating the original, which was very powerful and clearly the primary target of anyone with an SR if they could get their grabby things on both of these items in the same run. The point of that change was indeed to spur more variety, so… success!

The Shearcannon was an entirely new item in Beta 11, and clearly a big hit which absorbs a good chunk of new SR uses, though it was also a bit too common in Beta 11, so I imagine that value will come down a bit in Beta 12 as well.

Seeing a Core Expander on such a list in earlier versions would’ve seemed like a waste, but in Beta 11 it makes sense specifically for the new Exo build! So we know what those folks were up to…

The rest I’ll leave you to mull over :)

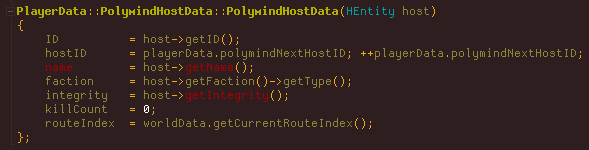

Exo

One of Beta 11’s new build options, this one a pretty complete transformation, is the Exoskeleton, specifically that one housed in Section 7. First you’ve got to be able to get there, but once you do, and under the right conditions, it’s a route to new gameplay and content on the back of a mostly OP build. I say mostly because still not quite everyone survives the results of using it :P

Here are some relevant stats I collected:

- 73.1% of runs that entered and survived Section 7 did not integrate with the Exoskeleton (technically they may not have even had the means, so it’s not always a choice)

- 0.8% of runs integrated with the Exoskeleton

- 11.0% of Exo runs did not make it out of Section 7

- 74.4% of Exo runs went on to win

- 80.3% of those winning Exo runs were extended wins (67.3 of those earned a ++, 32.7% earned only one +)

Exo runs are definitely easier once you get to that point, especially for experienced players--I got my highest score of Beta 11 in a build based on it without too much difficulty, and aoemica did a lot of extended streaking with it, though using separate patron builds so it doesn’t show up in the data here.

It might see more adjustments in the future to increase the challenge, but for now it’s kind of a backup option providing something else to fool around with if you get to that point and can’t carry out your original plan, or a way for some players who have more trouble with some very hard extended areas to still see them in some capacity (without lowering the difficulty level and having to adjust to the other changes that come with that).